Undamming the Klamath

You may already be aware of and paying attention to the Klamath Dam Removal Project, but if not, in brief, the four lowest dams on the Klamath River are being removed after decades of activism from the tribes of the Klamath River to reclaim their human rights and relationship the river and its salmon. This truly excites me and gives me hope for the potential for change in the world through the power of restoring rivers and their natural ecosystem function. The fact that salmon may return to their historic habitat may turn out be one the most powerful stories of ecological regeneration in our time.

A few years ago, Maren and I spent time in the Klamath River area documenting the four dams that were slated to be removed starting the following year. We had been really following the story of Klamath dam removal for a while when we found out the long contested plan to remove the four lower dams on the river was approved. I knew we had to get involved or try to document it. I thought it could make a really powerful moment for the film we were filming at the time: a great example of the intersection of ecology, food, indigenous rights, and food-ways. We spent a few days traveling from the mouth of the Klamath River, following the river inland to the dams that had, since the 60’s, been causing a catastrophic decline in the health of the salmon species that live there.

We thought we were lucky to catch onto the story early on enough to be able to document the dams before the removal. We also tried very hard to reach out to experts, scientists, Yurok tribe community members, etc. In the process of all this, we realized what a big and powerful story this was, and that ultimately the whole thing needs to be its own film, not just a side story in ours. To make a film solely on this topic, we would have had to relocate to the area and work full-time to follow leads and develop relationships with everyone involved, which would have been incredible, but ultimately impossible given all of the other topics we were exploring. Alas, we realized there was no way we could make a worthwhile film due to time, energy, and financial restrictions, and resigned to following the story the best we could from afar, hoping that someone would do the story justice in a film. Luckily for all of us, someone indeed is — and they appear to have tons of experience making films about water, river restoration, salmon, and environmental justice. They look like an incredibly talented team of creatives.

It has been a exciting story to check in on periodically, and sing the glory of dams being removed. As of now, it looks like one dam has been completely removed and three more are in the process of being removed by the end of the year. Once they’re gone, the real work of restoration begins. Volunteers have collected millions of seeds of native plants including acorn trees (famous for being a staple in the diets of many Native American tribes of California) and are planting these seeds in the soils of what used to be the reservoirs. Additionally, other types of monitoring projects are being implemented to continually evaluate water quality, fluctuating phosphorous levels, etc. It truly will be one of the most important events in ecological restoration — maybe ever.

“We are about to witness healing on a major scale. Dam removal is the best way to bring a river back to life. The Klamath is significant not only because it is the biggest dam removal and river restoration effort in history, but because it shows that we can right historic wrongs and make big, bold dreams a reality for our rivers and communities.” — Dr. Ann Willis, California Director, American Rivers

I have combined some of our footage of pre-removal dams with some footage of their removal from Swiftwater Films in the video below.

If people can heal this extremely degraded environment, it opens up the possibility for so much more good. Swiftwater Films has been given unprecedented access to all of the major players, and to document the dam removal, and we look forward to seeing their film when it is completed.

The Factory Farming of the Sea

Recently, Grist reported on a recent FAO report that found that in 2022, for the first time, more fish were farmed than were harvested from the wild. Aquaculture production (including the harvesting of algae) tipped over to 51% of the 223.3 million metric tons of animals and plants harvested from the oceans.

Because all fisheries on Earth have been discovered, and thus either exploited or protected, the only growth in the seafood industry will necessarily come from aquaculture. We’ve written about this problem before after we saw salmon farming first-hand in Norway in 2022.

There are tremendous problems with the global seafood industry, as highlighted in the Grist article. To add on to it, fish confined to pens develop health issues like sea lice, leading to increased pesticide use in the sea. The pesticides invariably leech out into the surrounding environment, disrupting ecosystem function. Excess nutrients around the farms also pose an ecological issue, particularly when fish are being fed things like soy pellets. Additionally, farmed fish have a weaker genetic makeup than wild fish, and they often escape their pens and breed with their wild counterparts. The same issues arise with hatchery fish — fish born and bred in man-made baby fish warehouses who are then released into fisheries when they mature. Their development is weakened by the artificial environment they’re born into, so they don’t have the same level of fitness as a wild fish. Those domesticated genetics are then passed down into wild fish populations, weakening them.

Industrial wild harvesting is also not sustainable. Fisheries are overfished, and bottom-trawling is incredibly destructive to non-targeted habitat and wildlife. Overall, the issue of conventional fish production has extremely negative externalities, making the solutions all the more difficult to prescribe.

We actually very seldom eat fish unless we’re in a coastal city. The reason for this is that otherwise, its almost impossible to avoid eating farmed fish, of which its healthiness is in question — especially fish that are fed fish-meal from the Baltic Sea. The Baltic sea is one of the most polluted ecosystems on Earth, and the way that toxins bioaccumulate in fish means that, when contaminated fish are fed to farmed fish, the contaminations continue going up the food chain. Additionally, factory farmed fish come with all of the same baggage as factory farmed livestock — they’re fed a limited, unhealthy diet; their lives are cruelly confined and ended as if they are mere mechanism; and rather than being a productive member of their environment, the way they are raised by us harms their environment. As is in the case of factory farmed land animals, it’s very challenging to follow the food chain and be able to verify that what you’re eating wasn’t being fed something toxic.

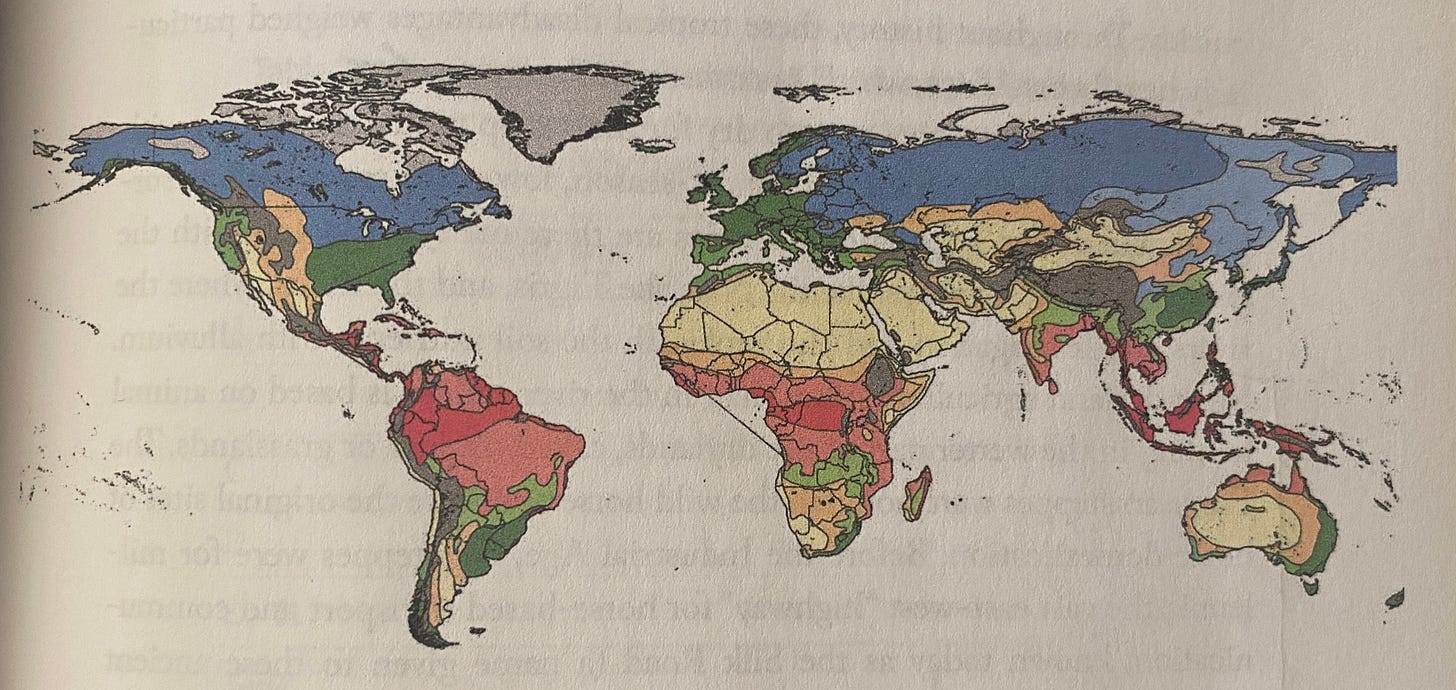

Of course, Grist’s solution for this is planet-wide veganism, based entirely on carbon emissions produced, ignoring the negative externalities of such a switch, such as: increased industrialization of the food system; increased food insecurity for anyone who doesn’t live in the green zones (see the Figure below), which are the temperate areas suitable for industrial agriculture; the prevalence of obesity and malnourishment due in large part to an abundance of processed “trade” foods and lack of access to fresh, whole foods; and the problems of an increasingly global food system based around commodities such as wheat, soy, and maize.

From our point of view, its the industrialization of the sea that is the problem, just as it is with the land and animals. We can’t install solar panels on fish farms, as Grist reporter, Frida Garza, suggests in this article, and really think we’ve solved the problem. This is not a technological problem — it’s a cultural problem.

It’s a cultural problem that it’s easier to buy flown-in New Zealand, Scottish, and Norwegian farmed salmon in the grocery store in Crescent City, CA than it is to buy local salmon. This is a result of a global, industrial food system being privileged at the expense of local food systems.

How to “feed the world” is the question that is always brought up, in spite of the fact that, due to the industrialization and globalization of the food system, roughly a third of the world’s food is wasted every year. Again, is this merely a technical problem, or could it be a cultural one?

This is a complex problem, and one that can’t be reduced to simple measures of carbon emissions or simple solutions like planetary veganism. The origin of the problem resides deep in the very structure of our civilization, and will not be easily disentangled. It seems that whenever we have to take for granted the industrial food system, the more farcical and impossible the solutions seem.

The Infinite Game of the Garden

This past week we released a new episode of the podcast discussing the book Finite and Infinite Games by James P. Carse. This little book has been widely disseminated, but also widely underestimated in its value because of its pop-culture reception.

In this episode, we discuss the deeper nuggets of insight within this complicated book, which helps add new language to a worldview that will allow us to live within nature as participants in a game rather than opponents in a war for dominance.

Thank you for your attention. If you’d like to support the project and gain access to future full podcasts, essays, and videos without ads, and be able to comment on posts, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or joining us on Patreon for as little as $5 a month.

As a PhD at Stanford that wrote on this for my honors thesis in undergrad and lived the fish kill and protests and ceremonial continuances that guaranteed water to flow through the basin on the Trinity River side, thank you for writing this. Big fan and I hope a connection between us happens soon.