Perfecting Enclosure

“At the heart of the Western way of seeing, and the heart of creating this big economic Machine has always been a process of enclosure.” We sat with Paul Kingsnorth in his small writing cabin in west-central Ireland, birds chittering outside in his garden. We were talking about how, in order for the English to colonize the rest of the world, they had to perfect it here, on these lush, boggy islands, to their own people. “Common land had to be taken from people here and had to be given to economic actors, to aristocrats, and land estates to factory owners, et cetera… we had to centralize and control resources and land in the West before we could go out and impose the same model on everybody else.”

In much of Paul Kingsnorth’s writing1, he uses the example of the Luddites, and the unfortunate modern mischaracterization of their movement as simply being “anti-technology.” On the contrary, the Luddites were using modern looms to create textiles. Their culture was based around a cottage industry of artisans, and when the factory culture of the industrial revolution came in with its massive machinery, consolidating the means of production, and all of the money to one factory owner, the people resisted. In their rebellion, they started smashing the factory machinery, which has been twisted and narrativized to label them as “anti-progress.” In reality, their livelihoods were being stolen from them by some foreign aristocrat, and they were being forced to work in the factories to pay their rents and afford to live. Their entire way of life had been enclosed upon.

“So, again, it wasn't simply that the objection was to new technology,” Paul told us. “The objection was to the mass destruction of their way of life.” The Luddites were resisting being turned into cogs in some alien, inhospitable machine. The Luddites were fighting for their right to choose their livelihood — their right to freedom, to living how they wanted to.

The enclosure was not only upon the lands, but also the soul.

There were thousands of such rebellions around England at this time, and many before throughout the world. In fact, this has been the entire trajectory of our now global civilization: enclosure, resistance, and ultimately, assimilated uniformity and simplified control. As Tyson Yunkaporta wrote in Sand Talk, “The Sumerians started it. The Romans perfected it. The Anglosphere inherited it. The world is now mired in it.”2 People always resist enclosure, for as long as they can. And the oppressors always use some modification of “progress” as being the justification for it needing to be done. What is amazing is how every time it’s done, the world at large finds a new reason to agree with these justifications for colonization. Back in the time of the Luddites, it was modernization. In Roman times, it was the project of civilization. For the Sumerians, their rule was ordained by the gods.

This time, it’s to reverse climate change.

Enclosure in the Far North

“We cannot reverse climate change,” Per Jonny Skum told us. “We can only adapt.” He sat, kneeling before his stove in his lavvu, boiling reindeer meat for us to eat. His young daughter, Anna, was playing with one of their very patient Sámi dogs, putting her snow-goggles on his face and giggling.

We met Per Jonny a few hours earlier on the side of the road, about 45 minutes north of Alta, Norway to go to his camp deep in Kvalsund, where his family has had summer pasture rights for generations. Riding through white-out weather conditions, we were astonished to see how effortlessly Per Jonny managed to get us to his lavvu. He knew every nook, every bump, every crevice on this vast expanse of land.

He had just recently made the journey from deep within Finnmark, following his reindeer from their winter pastures to their summer pastures. It was the beginning of May, and ice cold. Perfect conditions, he told us, for the reindeer to start calving. If the calves are born in a storm, it’s a good sign, because the reindeer will immediately adapt to the harshest conditions on the mountain.

It had been a horrible winter, as many Sámi people told us. Early in the winter, snow was followed by rain and a deep freeze, locking pastures for the reindeer. Climate change is impacting the Arctic more than three times the global average, and with the weather changing, there are more bad winters ahead.

In the past, bad winters were unpleasant, but there were ways to adapt to this climate variability. The landscape was vast and unencumbered by roads and development. If one pasture was locked by ice, the reindeer could find a new one, and the people would follow. This year, they had to resort to feeding soy pellets to their reindeer, particularly the pregnant females, in order to keep them alive. Already, Anders Oskal, the Secretary General of the Association of World Reindeer Herders, told us, the Sámi are having extreme difficulties adapting because so much of their lands have been consolidated and enclosed upon.

And there are many more plans, all over Sápmi, to take even more lands in the name of climate change. Iron mines, copper mines, and wind farms threaten reindeer pasturelands, all necessary for a “renewable” energy economy. In Per Jonny’s case, Repparfjord copper mine threatens his ancestral pasturelands. In the case of the Jama family, in central Norway, across the fjord from Trondheim, the Føsen Vindpark has completely destroyed their summer pasturelands. An iron-ore mine is being protested currently by Sámi activists in northern Sweden.

There are other, less public encroachments happening as well.

In Jämtland, Sweden, the untrained eye will see a stunning landscape of forested steppes, with the beautiful mountain of Åre as a striking backdrop. It is absolutely stunning. What few people see, however, is that the landscape is completely unnatural. These “forests” aren’t forests at all, they are tree farms— monocultures devoid of life and biodiversity. Each time I’ve come to this region, I’ve never seen any wildlife, accept for one deer in a Sámi village.

There is wildlife, however, and they have ultimate priority: the predators. Wolverine and lynx are considered to be the most important in this landscape, but given the lack of natural prey animals due to previous enclosure by agriculture, forestry, and development, the wolverine and lynx have basically only one food source: the reindeer.

A scheme, written by conservationists in Sweden, called “performance payments,” provides monetary payments for reindeer herders based on the amount of carnivores that are born in a given season. They are then compensated for the amount of damage that is speculated to be inflicted by that carnivore in during its lifetime. In prioritizing the carnivores, 20-30% of a herders flock might be killed in one season by a single predator.

Per Eric was no exception. He showed us a photo of one of his reindeer. Her stomach had been ripped open, and her calf, not yet fully formed, had been pulled out and draped across her belly. Blood soaked the snow around her mutilated body.

He had spent every night this winter buzzing around his flock on his snowmobile, trying to protect his reindeer from this one wolverine that was terrorizing them. The cost of diesel alone was enough to send him into economic ruin, not to mention the lack of sleep. 30% of his flock had been killed by this one wolverine. He petitioned the government for a license to kill the wolverine to no avail. The Swedish government dragged their feet all winter, and Per Eric made the decision to fence his reindeer in until they could move to their summer pastures and be mixed in with the rest of the villages flock. In order to do this, he had to feed them soy pellets.

Whether it be because of the bad winter and lack of pasture, or to protect their animals from predators, many Sámi herders had to resort to feeding their reindeer soy pellets. A culture which husbands the most sustainable food source on earth, a creature perfectly adapted to its landscape, playing keystone roles in building permafrost and limiting surface albedo3, forced to import soy feed from Brazil to keep their way of life, and their reindeer alive.

It wouldn’t be until later, speaking to a young Sámi woman, that we would understand the true weight of this conflict. She told us the story that Sámi children are told, that when the reindeer agreed to be eaten by the humans, they did under one condition:

That they don’t kill them like the wolverine.

The enclosure upon the Sámi is more than just physical: it is a breaking of the agreement that the people made with these animals, that they would protect them and give them a good life. Forcing them into a pattern of needing to feed the reindeer pellets also negatively impacts this contract in the long term, because suddenly the reindeer are not behaving like reindeer. This process of enclosure has a negative impact on tundra biodiversity in so many ways. Yet, the culture who encloses seems to think that putting a monetary value on the losses of these keystone animals is sufficient. The equilibrium of these snow-covered ecosystems cannot be valued in such terms.

When agriculture, tree farms, and development decimate the prey populations, should the Sámi be the ones to pay for that with the lives of their reindeer? Should the Sámi, in the name of renewable energy and “reversing” climate change, be forced off of their lands, forced out of their way of life, just like the Luddites?

Should their lands be encroached upon to the point of making their sustainable way of life resort to extractive and unsustainable means?

Making the Sustainable Unsustainable: The People of Cattle

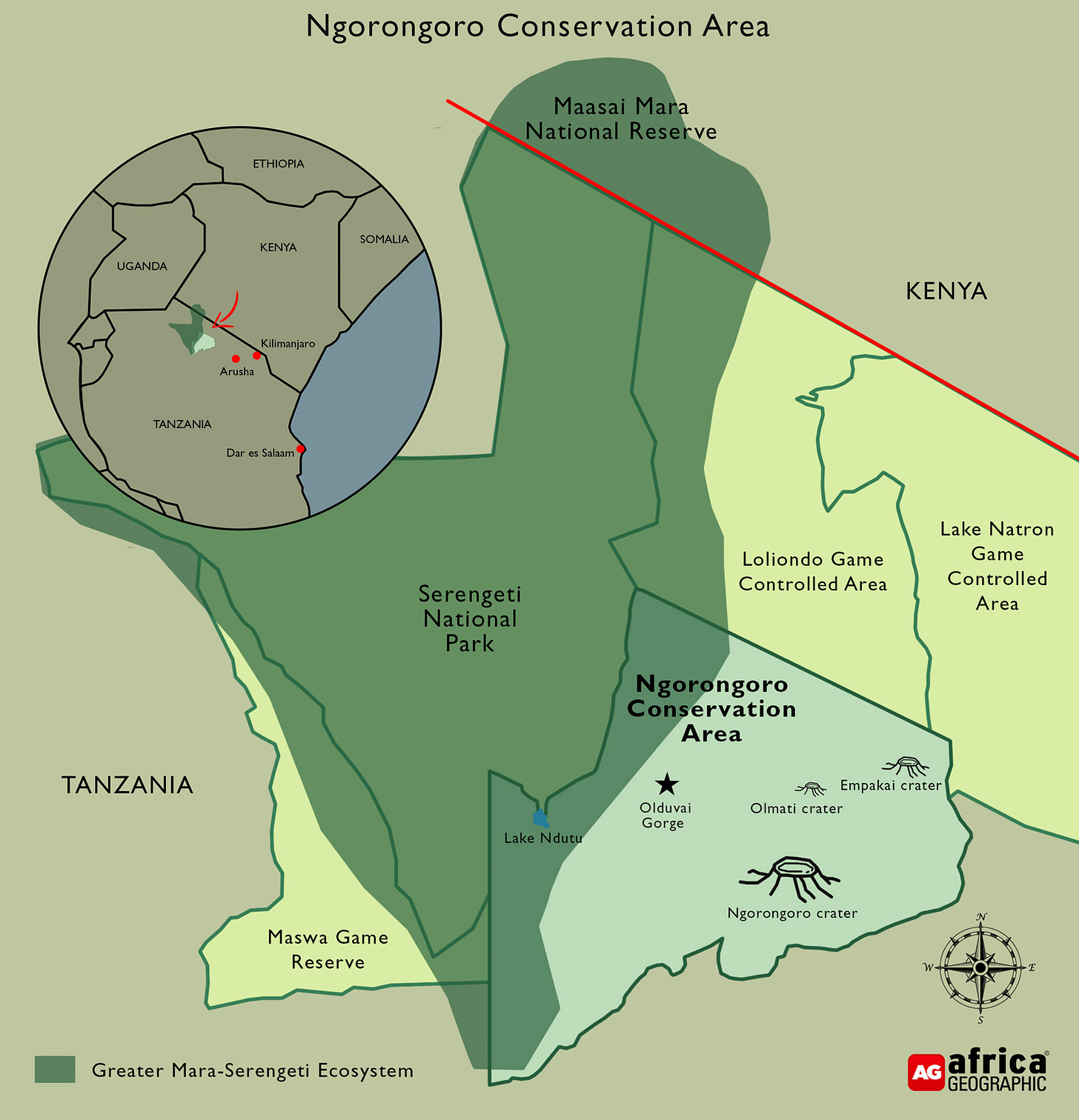

4,700 miles away, at the beginning of June, violence broke out in Loliondo Game-Controlled Area in Tanzania between the Tanzanian Police and the Maasai cattle herders. When the police arrived to demarcate the land for a game reserve, purchased by the United Arab Emirates Royal Family, a conflict that has been going on for decades, the Maasai people resisted, and live rounds were shot at the people. One police officer was killed in the retaliation, and 20 elders have since been detained. If the area is turned into a game reserve, where trophy hunting and the capture and export of wild animals will be permitted4, the Maasai people will be forced to relocate.

Again.

If it’s not horrible enough that the UAE has the power to purchase lands with existing villages and violently evict human beings from their homes, what few people, particularly in the West, understand, is this story actually has a very long history. The process of violent evictions has been going on since the installment of Serengeti as a national park in 1959 under British colonial rule5. The Maasai pastoralists, who had been herding their cattle on these lands for hundreds of years, were forced to relocate to what is now known as the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA)6. They were told at the time by the governor of then Tanganyika, that in the name of conservation, the government intended to protect the wildlife, but “should there be conflict between the interests of the game and the human inhabitants, those of the latter must take precedence7.” The Maasai’s rangelands decreased from 22,300 square kilometers to 8,292 square kilometers nearly instantaneously, and since then, violent evictions, militarized harassment, and economic disenfranchisement have become commonplace.

After independence and merging with Zanzibar, the old governor’s words began to fade into mere memory. Since this initial relocation into the NCA, the Maasai have been further dispossessed of land, such as being banned from herding in Ngorongoro Crater in 1974 (a reduction of 264 square kilometers of land), having their access to pasture, water, and mineral licks in Olromti and Embakaai Craters restricted in 2016 (28 and 50 square kilometers respectively), and the 2019 banning of livestock in the Northern Highland Forests and other key ecosystems like Ndutu marshes, which amounts a loss of an additional 1,242 square kilometers of land, as a conservative estimate.8

As pastoralists, this is a significant loss for many reasons. More than 80% of Maasai earn their livelihoods from pastoralism9, so restricting their access to key pastures causes overgrazing, which never would have been a problem in the past when they were able to graze all of the Mara-Serengeti ecosystem. As Kaj Århem explains in Pastoral Man in The Garden of Eden:

“Land use is transhumant, which means that grazing areas are seasonally kept fallow to allow for grass generation and to reduce grazing pressure. Rich grazing land is typically used during the dry season and left to recover during the wet, when people and livestock move to lower-potential areas.”10

In an ecosystem that coevolved with pastoralism for thousands of years, this can also have devastating consequences for the landscape. Without cattle grazing and the banning of controlled burns, vast swathes of these ecosystems are suffering from bush encroachment and invasive pioneer species.11 This iconic savanna ecosystem is transforming, and that might not be a good thing. According to a recent study12, the human development that is being forced onto the perimeters of the protected areas is “squeezing the wildlife in its core” causing disruptions to the equilibrium and negatively impacting wildlife.

“When the land area available to local people shrinks because of dispossessions and evictions implemented to expand protected areas, more human activity becomes necessary in the remaining areas bordering protected land.” —Teklehaymanot Weldemichel et al, Conservation: Beyond Population Growth

This disequilibrium is a direct result of the human rights violations of evicting the Maasai from their lands. Yet, the governing bodies of Ngorongoro, the government, and conservation NGOs (who offer safaris and trophy hunting) point to the Maasai as the main driver of ecological imbalance, pointing to their population growth as the largest problem. In truth, estimates say that within Ngorongoro there are only around 90,000. In Truth, Falsity, and Mismanagement, a report written and compiled by Maasai people, they also disagree with this assessment, stating:

“To the Maasai, the mentioned issues are just a manifestation of multifaceted problems known to exist as a result of ecosystem unconscious tourism investment.”13

This “ecosystem unconscious tourism investment” often includes prioritizing rich tourists over local people, including making concessions for the environmental degradation of their encampments, roads, and abundance of safari vehicles.

Enclosure has forced the Maasai to abandon their ecological practices of transhumant animal husbandry. Århem explains the consequences of this:

“The Maasai and other pastoral groups in Tanzania have been pushed out onto marginal lands, often being forced to use on a year-round basis grazing areas which they previously used only for wet season grazing. Poverty and a widening gap between prosperous and poor pastoralists have turned many pastoralists into agro-pastoralists and urban squatters.”14

Due to the Maasai being forbidden to practice subsistence farming since 1975 as well as their animal husbandry practices becoming less and less tenable, starvation and malnutrition are creating a “multidimensional poverty and chronic dependence” on aid and a globalized economy. Maasai villagers are arrested for “improving food security” for their families15, and face bails that they can hardly afford.

Without access to adequate pasture, water sources, and mineral licks, cattle don’t produce enough milk, which can account for up to 75% of their diet.16 Due to the respect they have for their animals, they do not drink more than their fare share from their cattle, making sure the calves have enough milk to thrive17. So, the people are forced instead to trade their animals for maize to supplement their diets, or rely entirely on aid.

The assault on the Maasai way of life has been cruel, violent, and inhumane. This recent violence in Loliondo follows the recent state-sanctioned burning of 185 bomas in 201718. Dispossessing people of their land and destroying their homes is egregious on its own, but beneath the surface, we can see another common story playing out: the investment in poverty as a justification for colonization.

Investing in Poverty: the Process of Suffocation

While violent, publicized evictions are indeed happening in Ngorongoro and Loliondo, a stealthier, more insidious process is happening in the shadows, to the degree that visitors of this area may find themselves agreeing that the Maasai are the problem.

We spoke to Maasai human rights lawyer, Joseph Moses Oleshangay, and he told us in no uncertain terms that the state is “investing in poverty, not alleviating poverty” to ensure that conditions are so poor that the people will relocate by their own accord.

In Making Land Grabbable, scholar Teklehaymanot G. Weldemichel describes this quiet process of suffocation:

“… not all landgrabbers always evict people as evictions may galvanize media attention and resistance. In some cases, local people are enclaved within the appropriated land and left to continue their lives in smaller spaces… a tactic that only postpones the problem of how people will survive on limited or no land, a problem that may become evident in the next generations. In others, displacement can be an “in situ displacement” or “economic displacement” in which local people are not physically driven out of land, but find their lives made difficult due to restrictions placed on their production practices.”19

Due to this investment in poverty, the Maasai have been made destitute. Because of their expulsion from their ancestral rangelands, the lands around their villages are desertified and degraded. Water scarcity is a real problem (as is typical in most places surrounded by industrial agriculture), and the Maasai are routinely harassed and arrested for “breaking in” to now-forbidden areas to water or feed their cattle. The people are chronically undernourished, as it is “considered greedy and wasteful to strip too much milk from the cow: the need to allow the calf enough milk for healthy growth outweighs short-term desire for more milk to feed people.”20 The survival of their already thin and undernourished cows takes precedent over the people.

Weldemichal explains the incomprehensible restrictions on the Maasai in the following terms:

“While local people can stay within the NCA, they can only do so if they practice pastoralism, as it is the only activity that is considered compatible with wildlife conservation. At the same time pastoral practices have been made difficult through the imposition of restrictions on access to grazing on important parts of the conservation area. At the same time, local people are not allowed to settle in fixed villages, but seasonal mobility is also curtailed. Locals argue that such contradictions in conservation policy and practice resulted in increasing poverty and dependence, which are again used by the state to legitimize resettlement.” 21

What is most insidious now is that the narrative is being deliberately formed: the Maasai must be relocated for their own good.

They must give up their way of life for their own good.

In the name of “lifting” the Maasai out of the artificially imposed poverty, the state is trying to convince the Maasai to start doing conventional agriculture using breeds of cattle that are not suited for this ecosystem nor a pastoral existence.22 Conflicts with wildlife have become more common as well, with lions preying on cattle at unprecedented rates. In fact, the same “payment performance” program that exists in Sweden is being proposed in Tanzania as a means to compensate for cattle losses. For a people who revere cattle, and whose entire livelihood is based upon cattle, it’s yet another imposition upon the Maasai which invalidates their way of life. Additionally, claims about illiteracy underpin the “necessity” of relocation, despite the fact that the imposition of enclosure and government malfeasance is a cause of these conflicts.23

In the documentary film Tanzania: The Royal Tour, American journalist, Peter Greenberg jet-sets around Tanzania with their president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, going on safaris, visiting tanzanite mines, and meeting with the Maasai. Narrated over aerial footage taken from their helicopter, Greenberg looks down on the Maasai villages, which look dusty and devoid of moisture, expressing fascination about these “primitive tribes hanging onto their traditional values,” and then says, “over the years, the Tanzanian government has tried to persuade the Maasai to become traditional farmers or ranchers, but they’ve persisted in clinging to their ancestral ways.”

“Persuade” is a really interesting way of saying “suffocate.” What the film does not mention is that the Tanzanian government (along with UNESCO) has been freezing access to critical infrastructure like hospitals and schools by suspending funding to these already decrepit and insufficient accommodations. They are instead investing billions into the relocation efforts, building houses and other infrastructure hundreds of miles away so that those who “voluntarily relocate” can live like “other humans” (quote from Tanzanian Deputy Minister Masanja)24. There have even been attacks against their cattle, when the government provided poisoned salt licks after banning them from pastures with mineral deposits as a “destocking strategy”25.

“It gives the impression that this is world heritage, without you,” Joseph Moses Oleshangay said to us.

It is abundantly clear that, for the Maasai, the assaults are coming from all angles. Their land is getting smaller and smaller, and with it, their culture, their way of life, and their dignity. Plans to relocate the Maasai may take them over 400 miles from their sacred mountain, Joseph told us, Ol Doinyo Lengai: The Mountain of God. Ngorongoro residents have never heard of these far-off lands before, and yet that is where the government, corporate, and NGO interests wish to place them.

As Americans know from our own history, land displacement is cultural genocide. Assimilation is genocide. Examples from all over the world should remind us of how inhumane this process is: from suicide rates among the Guarani that are 19 times higher than the national rate in Brazil to alcoholism and drug addictions ravaging dispossessed aboriginal people worldwide to a disproportionate degree.

This land-grabbing is only made worse by the “green” veneer it has adopted.

Green-grabbing: Dishonoring The Best Available Knowledges

“Colonial conservation, also known as Fortress Conservation, rests on the racist misconception that indigenous people cannot be trusted to look after their own land and the animals that live there. Its proponents view the original custodians of the land as a “nuisance” to be “dealt with", instead of as experts in local biodiversity and key partners in conservation.”— Survival International

Fortress conservation, as Gatu wa (John) Mbaria, co-author of The Big Conservation Lie, wrote in the Guardian last week, is primarily cordoned off for the wealthy to use “swathes of land as their playgrounds.” These “protected areas” allow for tourism but disallow local people to live within them. Tanzania is the most “protected” of all countries on Earth, with nearly 40% of its land under some kind of legal protection. What few people recognize, however, is that huge swathes of these “protected” lands are specifically for trophy hunting.

For example, in the Ruaha Game Reserve, you can pay $76,450 to hunt a lion. Clearly, this activity is the province of the rich, and oftentimes, foreign. Wealthy people can hunt exotic and endangered wildlife all over Africa, and the safari encampments and other manner of tourism based development is entirely permissible, but the bomas of the Maasai are targeted and burnt down “in order to preserve the ecosystems in the region and attract more tourists.”26

Clearly, there is a disconnect here. The affluent face less scrutiny than local people in the face of conservation, even though it’s the local people who are most willing to adapt and change their ritual practices when it becomes unsustainable, such as limiting, or in some cases ending completely, rite-of-passage lion hunting. Turns out, as long as you’re rich enough, no one will bat an eye if you lure a lion into a blind and kill it with a rifle (in fact, you’ll be praised for your bravery!), but if you hunt one with only a spear as part of your heritage, you’re a criminal who hates wildlife.

The perversion is deep. Westerners have long fetishized African wildlife, either in wanting to protect them, or hang them up on their walls— sometimes both27. The real question is, why do Westerners assume that they have more of an interest in protecting wildlife than the local people who subsist off the land do?

As Anders Oskal told us, “No one has a stronger interest in us in preserving these lands and these forests, these mountains, this Tundra.” No foreigner, myself included, should have more input in the future of a landscape than the local people who have stewarded the land for generations. “The Maasai conserve nature because they live in it, nature is their life.”28 Unfortunately, due to tourism and romantic films about Africa, many foreigners believe they have an equal stake in the Maasai-Mara ecosystem, and are easily persuaded by the narratives that exist to justify the evictions, regardless of how untrue or lacking in context they may be.

One of the biggest and most pernicious myths about conservation is that the tourism serves the local economies. Rarely is this the case. Local people are chronically disenfranchised from conservation and tourism efforts. The report, Losing the Serengeti, by the Oakland Institute found that of 548 employees of NCA, only 8 were residents of Ngorongoro, and a report from the 2004 found that, “while NCA earns well over half all Tanzania's returns few Maasai can access tourism-based livelihoods or share that revenue despite national policies requiring it to be shared with local communities.”29 This is still true today. Ngorongoro, which allows Maasai residents, brings in more tourism than even the Serengeti, which disallows Maasai residents, generating almost $62 million for Tanzania in 201930. In fact, most people come to this area because of the Maasai presence, yet the Maasai receive little, if any, benefit.

“The myth of ‘protected areas’ takes away not only our rights as people, but our ability to exercise our responsibilities related to land. Our symbiosis that connects us with spirits, animals, plants, water and land will be disrupted if this land is taken away from us.” — Maasai activist and community representative, Forest Peoples Programme

This situation of disenfranchising the Maasai in conservation efforts has only worsened today, despite the compounding research that local and indigenous people already steward the worlds biodiversity, and alienating them has degrading affects to the landscape.

Luckily, over the decades, there have been many anthropologists and ecologists who have corroborated what the Maasai know to be true: that they belong in this ecosystem.

An analysis done in 2018 concluded that “scientific evidence increasingly shows the compatibility of extensive livestock keeping with biodiversity, and even the important role of extensive livestock in keeping very relevant ecosystem functions” and recommended that “knowledge on pastoralist systems should be improved among NCAA (Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority) and any other stakeholders working on nature conservation in the district.”31

In Pastoral Man in the Garden of Eden, written in 1985, Kaj Århem described the equilibrium of the Maasai in Ngorongoro in the following terms:

“The Biblical story about the garden of Eden-about how man in the beginning lived in peace with every beast of the field and every bird in the air-naturally comes to mind when visiting the Ngorongoro Conservation Area in Tanzania. Here, semi-nomadic Maasai pastoralists coexist with a remarkably rich variety of wildlife in a natural setting of unspeakable beauty. One of the early travelers in Ngorongoro recorded how he here witnessed ‘an unforgettably beautiful scene of large herds of wildebeest, zebra and Grant's and Thomson's gazelles grazing peacefully together with the cattle of the Maasai people without showing any trace of shyness’ (1910). The same scene can still be seen today.”

He goes on to warn:

“But, as in the Biblical story, the pastoral scene is transient. The peaceful harmony conceals forces which threaten to shatter it. Man's own strivings for betterment and the development and conservation policies of the state tend to separate man and nature. Ambitious development goals increasingly set man against nature, and the creation of National Parks and Game Reserves alienate indigenous people from their land by setting it apart-as islands of nature-for international wildlife tourism.”32

In 1991, ecology and anthropology researchers Katherine Homewood and Alan Rogers from Cambridge stated in their book Maasailand Ecology, that, “any move to expel the Maasai will be counterproductive to long-term conservation interest, quite apart from being a major abuse of human rights.”33

The authors of The Serengeti Squeeze, the study which found cordoning the Maasai to border areas had knock-on affects to wildlife within the park, conclude with a recommendation of including pastoralists in the landscape more, not less.34

Even in the Arctic, with Norway having the only Indigenous Parliament in the world, the Sámi people still struggle to have their rights respected and their livelihood valued for the ecological and cultural richness it provides. News headlines like “As A Business, Reindeer Husbandry Cannot Be Defended” proliferate through a progressive consciousness myopically fixated on “green” development, wherein the Sámi and their land rights are perceived as an impediment to progress. Cases like Føsen Vind, which have dominated the life of Maja Kristine Jama (who will soon be featured on the podcast), a member of the Sámi council, and her family, fall on deaf ears in a culture that puts attempting reversing climate change (at all costs) at the center of its value system.

In a pivotal report entitled Human Rights Protection against Interference in Traditional Sami Areas which outlines Sámi rights in Norway following the Føsen case, written by Lars Johan Strömgren, Gro Nystuen and Petter Wille, they state:

“Increased demand for raw materials, energy and the transition to “green energy”, together with new technologies, have led to increased development of wind power and the need for increased extraction of minerals, which in many places threaten indigenous peoples’ traditional livelihoods and economic bases.”35

Again, actions are being taken on “behalf” of biodiversity and climate change, but are actively harming the people who always stewarded and lived in harmony with those landscapes. It obviously makes little sense to blow up mountains or cover them in machinery in the name of saving the planet, but it also doesn’t make sense to banish local people from their ancestral lands in the name of “protecting” it.

What should instead be centered is locality: local climates, local ways of life, and local resilience. Enclosure always comes from elsewhere, with goals that are anti-local. The top-down approach of either conservation or renewable energy creates a multiplicity of negative externalities, as well as denying the well of knowledge that local people can provide when it comes to protecting and stewarding their specific lands. Reindeer herding is chronically ignored, not only for its validity as a livelihood, but also for its ecological benefits. Grazing and fire management are necessary for the savanna ecosystems with which coevolved with humans. When we disregard that local, “human-coupled” ecosystems serve an integral role in preserving biodiversity, we start to have the deranged idea that these local people are the problem, rather than those best equipped to understand and interact with the landscapes in question.

“In all the challenges before us are of such proportions that we have to use the best available knowledge to be able to cope, to adapt, and be resilient,” Anders told us. “In the Sámi language, we have 318 different words for snow.” He laughed when he explained how Swiss and Austrian avalanche researchers had only identified 40 unique terms, and they were astonished by the breadth of reindeer herders knowledge. “Some of these terms (in Sámi),” he said, “require a full page in English to be translated.” He was generous in saying how valuable the scientific data was that these avalanche researchers had compiled, but still made it clear how combining these knowledges will be the only way to resolve the problems we face.

The Sámi language, the Maa language, and thousands of others can offer us clues to understanding how to combat localized climate change, clues that can never be uncovered in a clumsy, abstracted language like English. Severing people from their lands also severs them from these specific languages that have been molded by landscapes. Without this knowledge, we may never be able to adapt to climate change and deal with its extant causes. This language, Anders told us, coupled with indigenous ways of knowing, would be an invaluable complement to science.

In Losing the Serengeti, the authors write:

“Without access to grazing lands and watering holes, and without the ability to grow food for their communities, the Maasai are at risk of a new 21st century period of emutai (“to wipe out”). This loss – of culture, knowledge, tradition, language, lifestyle, stewardship, and more – is unfathomably large.”36

We’ve already lost so many languages in the process of colonization. Missing from the Earth forever is vocabulary that is needed for us to understand where to go from here. We have to protect what’s left, and enable indigenous languages to continue being taught. That sort of literacy is far more important than the illiteracy which is being wielded to justify evictions from Ngorongoro. Literacy and knowledge exist in myriad forms and should all be respected. Even memory and oral cultures may serve us more in the long-run than having a narrow view of literacy or a Western education as a panacea to resolve the issues of our time. Dispossession from indigenous ways of knowing, speaking about, and seeing the world endangers us all.

Enclosure endangers us all.

When Land is Enclosed, So Are We

“It is absolutely at the heart of the Machine: the control and the enclosure of resources, and therefore the control and the enclosure of people fundamentally,” Paul Kingsnorth said to us.

This sickly process of stripping more and more freedom from the people is so shockingly ubiquitous that we hardly notice it. This is just the way things are in the world. There are the “civilized" and the “primitives” who need to be “civilized.”

What being civilized means, and has meant since the process began, is to be enclosed upon. Enclosure has a duality to it. When your lands and your way of life have been enclosed upon, where do you go?

You go the only place you can go: into a new enclosure.

There used to be hinterlands to escape to, undeveloped lands on the fringes where the not-yet-civilized could hide and be free to live their lives the way they wanted to. Those hinterlands do not exist anymore, so when your lands are taken, you have to be “put” somewhere. Whether you’re forced to settle on the outskirts of national parks, or you’re relocated to a foreign land, you have been placed in an alien enclosure.

“As areas have been deemed “protected” or transferred to new owners, the Maasai have been driven into smaller and smaller areas, creating a map of confinement that is as stifling and foreign to them as a zoo to a lion.” — Losing the Serengeti37

In Christopher Ryan’s book, Civilized to Death, he writes, aptly, “We are the only species that lives in zoos of our own design. Each day, we create the world we and our descendants are going to inhabit.”38 This zoo, he told us, “is very inhospitable to the animal that's enclosed there, which is us.”

What happens when people who never even knew the zoo existed are forced to live behind its glass walls? What happens when a people are uprooted, dispossessed, and forced to live in the dominant story that pervades our time? Can we blame them, and say they were swept up in a “pursuit of progress” like our culture, that they chose this fate? Or is it more true to say that the pursuit of progress swept them up, unrooting them, severing their ties from land, culture, and identity?

Enclosure is two-fold: it’s not only the lands that were once free that are enclosed, but the people, now homeless, uprooted from freedom, must be enclosed in something, too. What they find themselves shackled to and surrounded by is modernity, global capitalism, the Machine. Where else does a free creature go when its land has been stolen from it? This now homeless being must be put somewhere, in some foreign zoo, some cheap, insincere facsimile of what they know and remember.

When your cattle and ancestral pastures are taken from you, and subsistence farming is banned, is there such a thing as choice? When the only way you can feed your children is from maize-meal aid because your cows are too sick and skinny to produce milk, are you freely choosing this way of life? Or have you been suffocated into making a choice that you never would have made had you been free?

If the mark of this culture, as according to Daniel Quinn, is true, that what separates this culture from the thousands of others it has absorbed, colonized, and assimilated, is that the “food is kept under lock and key,”39 should the burden for the disharmony in the environment be placed on the zoo animals, or the zookeepers?

When we turn away from the enclosures that are happening today, we deny how this process has affected us as well. So many of us are like the lions, tigers, and gorillas who pace back and forth behind the 4-inch glass or metal bars staring listlessly out at the world, bewildered by this state of being captured by something ineffable, something we can scarcely comprehend. Some of us can be tranquilized into ignoring it, for a time. Many of us can’t help but notice that we have become entangled in something ominous, not by choice, but by birth.

It strikes me that the only thing that is worse than being born into the zoo is being born free and then slowly watching your lands being eaten and transformed into something unfamiliar and alien, and then, subtly, over time, you too are part of the enclosure, stripped of the culture that tethers you to your belonging in the world. Through suffocation or violence or a systematic denial of your right to practice your way of life, you find yourself enclosed.

This is why people protest all over the world, shouting such a simple demand: to have the freedom to live their lives the way they want to.

And as we’ve seen, this freedom has only made the world better and more beautiful. Local communities steward more biodiversity than any other groups in the world. The Maasai-Mara was built by herding people. The Arctic’s brilliance is due to the agreement between man and reindeer. The Great Plains, in their once incomprehensible fecundity, were shaped by people who revered and directed herds of millions of bison.

The Luddites weren’t protesting against technology: they were protesting for freedom. Freedom to make beautiful art and live in their villages and have control over the kind of people they wanted to be. Who wouldn’t fight against being forced into the factories? Who wouldn’t fight against being forced into a cage? Who wouldn’t fight, until their dying breath, to be free?

Freedom, above all, is choice. It’s the choice to either hold onto your heritage or abandon it. It’s the choice of which technologies to integrate into your life, and which to avoid. It’s the choice of which language you speak. It’s the choice of how you get your food. It’s the choice to pray to your gods and not someone else’s. The insidious problem with this duality of enclosure is that it takes away the ability to choose, and instead only offers illusions of choice— a banana or a mango so we don’t beat down the doors to our cages.

Joseph messaged me after our talk, sharing with me and reference recently filed in the East African Court of Justice to fight back against “government injustice” in the NCA. The reference is signed with thousands of thumbprints of Maasai people. He added, “we are challenging ongoing eviction plan, violation or cultural and spiritual rights, extermination, systematic marginalization, systematic attack to Maasai identity, history, culture…” Against impossible odds, the Maasai are fighting back.

The Sámi fought back against enclosure, too, at Føsen, using Article 27 of the UN Declaration on Human Rights, which states:

“Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.”

This past October, after decades of fighting, the Supreme Court of Norway agreed.

They won.

The concessions remain to be decided, but the Sámi proved something — that indigenous sovereignty can prevail. Lars Johan Strömgren, a Sámi human rights lawyer and author of the aforementioned report, broke this victory down for us at the Sámi University in Kautokeino, Norway— this victory being the very first of its kind, but hopefully, not the last.

If anything, the history of enclosure is a history of freedom fighters, men and women fighting for something so fundamental to our humanity, something that many of us don’t even recognize we were born without, being saddled with a whole history of psycho-spiritual debt the moment we crested into the outside world from our mother’s womb, and yet, in so many myriad ways, we’re the lucky ones. The privileged few who may have the chance to see what is being done to the rest of the world and try to actually do something about it. Not to be a savior of some kind, but because if there is a rot that needs to be excised, it lives here.

Enclosure starts here: in the West. It starts with a belief system that has been imposed upon us which says that, in the name of progress, there is no cost that is too high.

“We won't question the notion of whether we're actually progressing towards something good. My feeling is that at the heart of the myth of progress is a fundamental desire for humans to be gods, effectively: to control nature, to control ourselves, to manipulate the earth at the genetic level, to effectively rebuild the entire world, to suit the modern mentality, the mentality of enclosure and control.” — Paul Kingsnorth

It is the same voice which tells us there is no alternative to this way of life, which needs more and more of the living earth and all its people, including us, being churned into living mechanisms whose sole purpose is to maintain its ascent to fictitious godhood… No.

As the world around us becomes more and more enclosed, so too do we. Soon we will have nowhere to turn. If the world is indeed destined to recede into some climate change induced hell-fire, I only ask this, for the sake of all of us:

Stop the enclosure.

Written by Maren Morgan

If you enjoyed this work, please consider sharing it with your friends and family.

If you have not yet subscribed to our newsletter, please click the button below:

If you would like to support the multimedia project “Death in The Garden,” please consider becoming a paid subscriber, or join our Patreon community.

Kingsnorth, P. (2017) Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist and Other Essays

Yunkaporta, T. (2019) Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World

Mittal, A & Fraser, E. (2018) Losing the Serengeti: The Maasai Land that was to Run Forever

Ibid, p. 16

Ibid, p. 4

Manzano, P. & Yamat, L. (2018) Livestock sector in the Ngorongoro District: analysis, shortcomings and options for improvement

Århem, K. (1985) Pastoral Man in the Garden of Eden

Oleshaudo, p. 54

Veldhuis, M. et al (2019) The Serengeti squeeze: cross-boundary human impacts compromise an iconic protected ecosystem

Ibid, p. 7

Århem, p. 22

Mittal & Fraser, p. 27

Århem, p. 67

Homewood, K. & Rogers, W. (1991) Maasailand Ecology: pastoralist development and wildlife conservation in Ngorongoro, Tanzania

Mittal & Fraser, p. 9

Homewood & Rogers, p. 38

Weldemichal, p. 3

Manzano, p. 18

Oleshaudo, p. 105

Ibid, p. 119

Ibid, p. 94

Mittal & Fraser, p. 21

Mbaria, G. & Ogada, M. (2017) The Big Conservation Lie: The Untold Story of Conservation Wildlife in Kenya

Oleshaudo, p. 109

Homewood & Rogers, p. 16

Oleshaudo, p. 49

Manzano, p. 38

Århem, p. 9

Homewood & Rogers, p. 265

Veldhuis, p. 6

Strömgren, J. et al (2022) Human Rights Protection Against Interference in Traditional Sámi Areas

Mittal & Fraser, p. 33

Ibid, p. 6

Ryan, C. (2019) Civilized to Death: The Price of Progress

That was an absolutely incredible read.

I don't even know where to start.

You touched upon deeply nuanced issues with great insight and understanding of the sweeping injustice that devastates Indigenous peoples around the world.

It is certainly an incredibly grim scene here in Australia, where most Australian's still believe that our First Nation's people are of a lower race and that their high rates of alcoholism and incarceration are of their own doing.

During your essay I was left wondering about the tragic nature of this undoing - that this devastation is not wrought from acts of evil or calculated intention, but instead from the hearts of potentially good people trying their best to do the right thing by the environment. I almost feel that this is worse than there just being a room full of bad guys that we could more easily identify and bring down.

Instead, the movement of sustainability has massive momentum of its own, even when not co-opted by insidious corporate greed.

Thanks again for the writing, you guys need to write a book.

Eamon

Absolutely beautiful writing Jake and Maren! I've sent it to everyone I know in the conservation and permaculture fields in my little part of the world. I appreciate all of the sources that you provide, so I can go down a research rabbit hole!

I think in the end, the indigenous people who have been caretakers of the land for millennia ought to be valued and trusted with the continued care of that land, including decision making in future land use. Why would we pretend all that knowledge doesn't exist?