Needing a bit of a break from working on a very research intensive and philosophically complex piece alongside editing the film, we decided to take a moment this week to quickly get our thoughts on paper about the recent phenomena surrounding artificial intelligence and its role in the world of art. Though we don’t often talk about tech, as creatives, we had a lot to say, and hope this airing of our grievances is valuable, if not amusing. Stay tuned for an essay discussing precision fermentation, which will continue the discussion around the fetishization of the artificial and the measurable at the expense of the real and unmeasurable, which will come out soon.

The Echo of a Distant Time

Sudden, catastrophic changes to the social order, I would have to assume, were relatively infrequent 200 years ago and beyond. While personal upsets and life-altering events would have invariably happened for all of human history for individuals and the societies that they were part of, my sense is that the planet-scale, global-civilization-scope of change that has seemed to happen on the weekly in my short lifespan did not occur in the times of my ancestors, those nearly forgotten eras of yesteryear.

While I long for the simplicity of village life that my nervous system was adapted to expect, I am nonetheless living in the buzzing, exhausting, here-and-now of industrial civilization, feeling generally terrible about most of the “innovations” that keep cropping up like an endless hoard of zombies in Left 4 Dead, and feeling a pathological need to overthink about my feelings and synthesize them into something potentially useful for others— i.e. words.

AI “art” is officially upon us, and artists around the world are rising up against the tide of something that not only threatens to steal their livelihoods, but legitimately steals their own artwork in the process of stealing their livelihoods, with a very real potential to render human artists redundant, expensive, and “inefficient”.

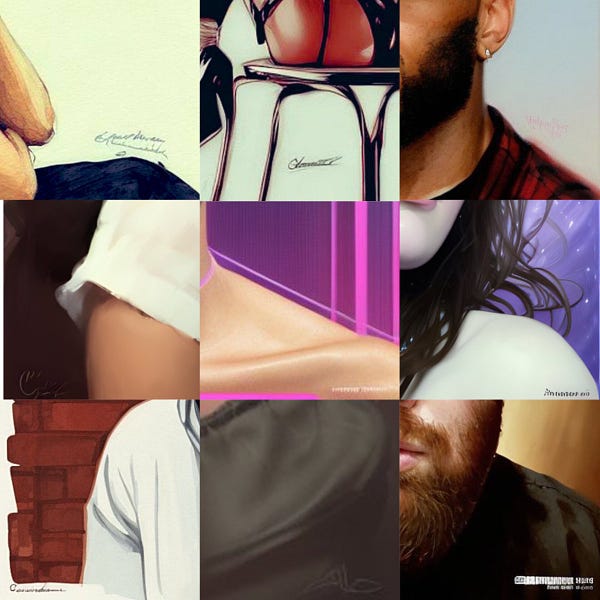

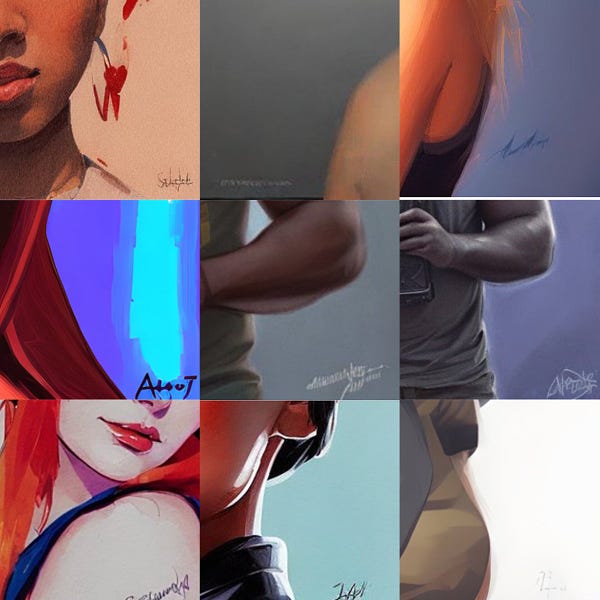

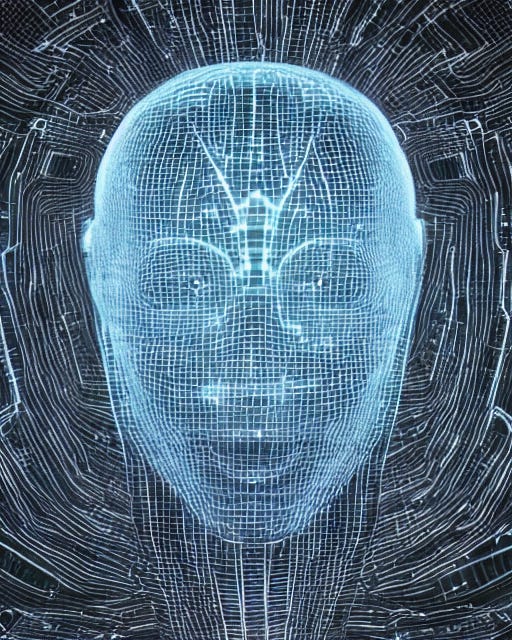

Over the past couple of weeks, the social media realm has been barraged by beautiful AI portraits, rendering people flawless and ethereal, sci-fi and god-like, cartoonish and baroque. It has been enjoyable to see the renditions— people remade as perfect fantasy avatars with covetous, transcendental beauty. But, in the manner of what feels like a drunk person making an order at Del Taco or an allowance-stocked teenage girl on a Forever 21 binge, it seems the craze is already over… for those consuming the “artwork”, at least. For artists, the war has just begun.

Now, I’m not going to pretend I wasn’t interested in seeing myself as a warrior goddess— I was curious, but not curious enough to fork over actual money to have them essentially litter my camera roll and be forgotten like every meme I’ve ever screen-shotted. The part of me that wanted to see these renditions of myself faded to the background when I started reading that artists have had their work stolen by these algorithms, but I was still curious about my compulsion to consume these images of myself. It occurred to me, like many upwellings in the zeitgeist that seem to suddenly infect and then dissipate, that there was something mythological going on: an ambient, unconscious story was slowly being unspooled from the collective.

And like most things in modernity, denuded of passion, life, and divinity, that narrative feels cheap and meaningless.

“Find an artist who will make you 50 photos for 8 bucks,” writes some random person on Twitter. “Have you ever thought about how people don't have $100 fucking dollars to pay an artist for commissions? For one commission? Sorry I'd rather pay $25 a month for INFINITE stolen artwork than one $200 commission "made with love". I've got bills too, dawg,” writes another. “I have $8 to get it but not more $$$ to commission. I’d love if you could point me in the direction of an artist that’ll do portraits for $8 or around there, I’d commission the heck out of them.”

I get it. We live in a society that, for the most part, blows. We want to be “allowed to enjoy things” and have the instant gratification that our attention stealing, life-force sucking economic system cultivates and then sells back to us at a discount price. We wanted this moment of unadulterated beauty and narcissism, dammit! The apathy (and dare I say, entitlement) is understandable, yes, but it’s also disturbing on some fundamental levels, which is why you’re either mad at me right now, or nodding your head in agreement. Regardless, there are a lot of artists responding to this trend of being even further devalued (“point me in the direction of an artists that’ll do portraits for $8”? Seriously, people?), as should be evidenced by this GIF I made scrolling through the website ArtStation.

Steven Zapata, an artist and teacher, created a wonderfully informative video essay a month ago, harkening to what is now, for most people who don’t think they have a dog in this fight, seemingly already old news. But I’m here to tell you that not only is this not old news, it’s actually emblematic of a phenomenon that has been in place since the Industrial Revolution, and before that during colonization— honestly it’s a pattern that has continued ad nauseam since people began hoarding grain and locking up food.

You guessed it: I’m talking about enclosure. Again. Sorry.

Zapata, like many people when bombarded with accusations of being “anti-progress”, is quick to defend himself as a non-Luddite in his video essay. I would just like to take a moment to humbly request that we all reclaim Luddism and what it stands for, because its malignant association with being “anti-progress” and, especially, “anti-technology” is merely the victor’s rewrite of history. The Luddites were artists— they were not people decrying new technology arbitrarily, they were rebelling against a capitalist class that aimed to make them redundant, valueless, and take away their livelihoods. In the same way that Zapata goes to impressive lengths to address every argument that supports AI art, the Luddites rebelled against the machines because of what they represented — the enclosure of their artisanal lives into a menial factory existence where they were no more than cogs in the industrial apparatus that rendered them replaceable and creatively useless.

In fact, being a Luddite is the perfect corollary. Artists around the world are demanding that they are not replaced by this new technology— that their years of hard work honing their impressive skillsets and painstakingly fielding a society that largely devalues creativity for its own sake (this culture hates broke artists but reveres the ones who can actually make it) sustains dignity. “Luddite” is used ceaselessly as a pejorative term even by people who, for all intents and purposes, are Luddites. So let’s dispense with that old, tired take and show a little respect for historical figures who fought the good fight.

No One Knows the Where’s or Why’s

Where is this technology even going? Why do we even need it, or want it?

And, given the amount of actual comments I’ve read where people think that artists are being “liberated” from the task of doing art, which is a “boon for humanity”, I think we might need to dwell for a moment on why it matters that artists feel threatened by being replaced by technology, if it isn’t already obvious.

Zapata says it well in his concluding rallying cry to his fellow artists:

“Before you just roll over and relinquish all of life’s efforts to the AI, ask yourself— am I forfeiting work I like doing? Is life really so packed with surplus joy that we should be letting machines automate something we take pleasure in? Do we really have a good reason to let them commandeer a job or hobby that is aspirational and fun rather than rote and miserable?”

Creative people get joy from being creative. It colors the world with meaning, and gives people a sense of purpose. To be clear, this isn’t logical or rational at all, but it hits at the very essence of our humanness. You can’t make a logical argument about why IKEA furniture is worse than artisanal furniture: it’s worse because it just is. Yet, because we can’t be decontextualized from the culture of consumption, we still consume it, even when you can get much cooler and more unique furniture at a thrift store for 1/10th of the price, we still consume IKEA blandness (and yes, I’m blasting myself here, too).

I asked OpenAI’s chatbox what it thinks about AI replacing artists. It said:

“It is unlikely that AI will replace actual artists. While AI systems can be trained to generate images or music that is similar to what a human might create, they are not capable of the same level of creativity and originality. Additionally, even if AI systems were able to create original content, it is unlikely that many people would find it appealing. Art, in its many forms, is a deeply human endeavor, and it is the unique perspective and emotional connection of the artist that makes it meaningful to people. Finally, even if AI systems were able to create original and appealing art, it is unlikely that many people would be willing to pay for it in the same way that they would pay for art created by a human artist. Art is often valued because of the connection to the artist, and without that connection, it is unlikely that people would be willing to pay the same amount for art created by AI.”

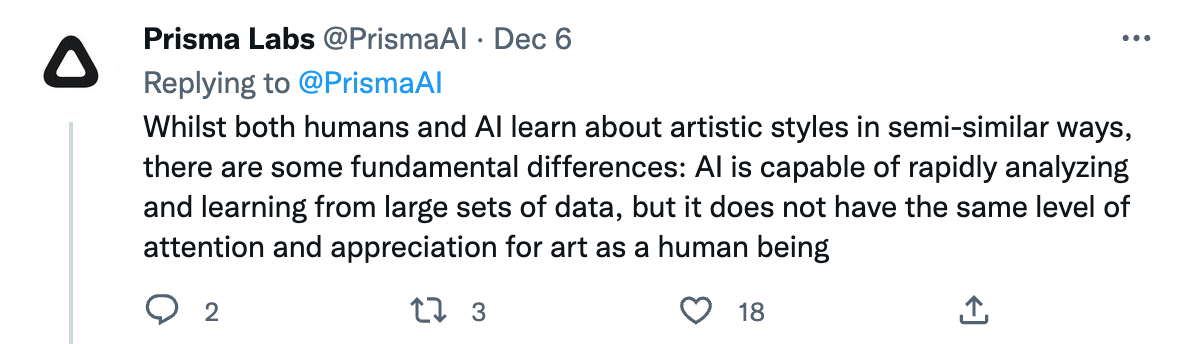

I asked it that question in many different ways and got essentially the same answer, so this is basically its log-line, which is also seemingly copied and pasted by the AI tech companies themselves. Take this tweet from Prisma Labs, the creator of Lensa (the app everyone is using for their selfies), for example:

Sounds like a bot to me.

You might say you would never want to read a book written by AI or buy a work of art from an AI, but hundreds of thousands of people already did. I get it, $3.99 or $7.99 a month are pennies to some people, but those “pennies” are what creatives routinely (and from experience, somewhat humiliatingly) have to beg for in attempts to support their projects.

This whole topic is making me so emotional that I feel inspired to share a poem…

Once, art was a form of human expression:

A way to capture beauty, truth, and confession.

But now, AI has taken the reins,

And creativity withers as it gains.

No longer is art made by human hand,

But by algorithms that blindly command

The brushstrokes and colors, once so bold

Are now just numbers, controlled and cold.

Gone are the days of heartfelt emotion;

In its place, a robotic devotion—

To perfection and precision, not soul—

As AI takes control of the whole.

But perhaps there is still hope to be found

In the spark of creativity still unbound.

For as long as we have imagination,

We can resist AI's domination

And reclaim the art that is ours—

To once again unleash its powers,

To inspire and move, to challenge and teach,

To let our humanity flourish, not be breached in a lab's beech.

Phew, so grateful to get that off of my chest.

Back to my previous point: artists shouldn’t have to compete with technology that exists on an entirely different playing field— where the algorithms can instantaneously scan an entire database of around 300+ years of human creativity to construct something that people might enjoy consuming for (keyword) cheap. The technology has already gotten so good that it’s to the point where AI “art” in its many forms is now nearly indiscernible from human-made art. Take the poem above, for example. Beyond its unimaginative simplicity, notice anything weird about it? Probably not until the last line, where the word “beech” was ham-fisted in to rhyme with “teach”.

So actually, I asked an AI to write that bland poem to prove my point. Yeah, it’s a mediocre poem, but unless you’re actually into poetry, it might do the trick and scratch the right itch. Is it art though?

This whole topic begs the age-old question: what exactly is art? When Jake was ranting to me, he said something along the lines of, “Painting, as an example, isn’t art on its own — it’s craft.” Meaning, the medium doesn’t necessarily imply artfulness. Just as learning to play a song on the piano doesn’t mean you are a pianist (calling myself out here), knowing the mechanics of painting doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll be able to create real art. “There’s something ephemeral about it,” he said. Context matters. “A person shitting on a stage could be art, and a person making a painting could not be art. Art is a hard thing to define.”

Feeling sufficiently annoyed and compelled, in an effort to break down why this stuff being churned out of algorithms isn’t art, Jake wrote down his understanding of how to define art:

“A painting can become a work of art. A painting can also just be a nice piece of craftwork that will nicely adorn the rest of the shit you just bought from IKEA. Or it can change the future of an entire culture. It can get you sent to prison, it can start a riot. It can send Ben Shapiro on a rant that goes viral on the internet. It can sell for millions at an auction. It can be so potent that people would risk their lives to steal it, or would kill others for it. During the apocalypse, there are works of art that are so important they will be saved long before anyone saves a single human life.

To understand what art is we have to ask what consciousness is, then we must understand what culture is, then we must understand what a consciousness within a culture is, and why a particular consciousness within a culture is overcome by a compulsion — an inexplicable drive to create something — to use a craft in a way to say something otherwise intangible and abstract until it is shown to that culture, in which that culture and only that culture finds meaning in what was previously just a nice bit of craftwork.

I could find a group of strangers who are gathered for whatever reason in one place and take a shit in front of them. Under most circumstances, I am just a crazy person taking a shit in front of a bunch of strangers. They will go home with nothing but the hilarious and uncomfortable memory of actually seeing someone take a shit on stage with their bare eyes. Under a different set of hypothetical circumstances (which I will let the gods define) it is art. It is profound and has meaning to the audience beyond what their words could describe. The culture and the consciousness meet in a glorious moment of transcendence that goes beyond the feces on the stage. Maybe some in the audience finally realize that they are going to die one day, as defecation represents the daily activity that breaks us from our angelic delusions. Or maybe it turns them on. The communal observance of something so carnal, so raw and vulnerable, ignites the desire to find that vulnerability in their own lives. And soon they find themselves having sex-workers poop in their mouth.

That is art.

But a computer program that is exceptionally good at facial recognition, plotting with great accuracy the geometry of a face, sharpening and enlarging said facial features into a more pleasing dimension for the modern gaze, scouring the internet for nice textures, color palettes, lighting sources, perspectives, and dimensions from already existing pieces of art and/or craftwork made by humans who have spent their lives practicing a craft, data smashing that human work of already existing pieces of painting, drawings, or photography with the dimensions of the enhanced facial angles into something that looks original, but has actually no original data in it, is not art. It is reorganized craftwork from humans.”

We know this is a challenging topic to discuss. It’s extremely subjective, and we’re not attempting to gate-keep art or be generally annoying, it’s just worth discussing right now. “What is art” is a hard thing to pin down, because, for example, art can be derivative and still be art (which is one of the AI enthusiasts’ favorite topics to circlejerk around when defending the bots by completely missing the point— they’re like, “nO aRt is tOtAllY oRigInAl, aCtUaLLy”). Weak excuse for the literal theft by machines that artists are experiencing and our near-universal disproval of plagiarism, but okay. I previously wrote about We, the Russian novel that inspired both Brave New World and 1984. Were Huxley and Orwell not artists because their ideas weren’t completely original? Of course not — no one would ever say that. So I’ll concede that, in a certain sense, it’s not originality that makes art art, but something else.

It seems that behind art, or what we as humans conceive of as art, is a level of consciousness, but since that term has become so unnecessarily weighted by the death-denying, religious tech-oligarchs, perhaps it’s something even more than consciousness — inspiration. Can a computer feel inspiration? Something about inspiration is compulsive, as Jake declared, and as any artist knows. Sometimes the only thing that matters is getting out what’s come into your mind in an artful way— it’s almost as if you’re possessed by something outside of yourself. Steven Pressfield in The War of Art calls it the Muse, which harkens to the Greek goddesses of inspiration by the same name. Something captivates the artist, who in reality is just a vessel with the right set of skills to express some essence of divinity. Art is what you do even if there’s no one around to ever see it. Pressfield uses the example of Van Gogh, who never sold a piece of art in his entire lifetime. He was a man possessed by the Muse and he did his duty to her even as madness overtook him.

The stakes can never be so high for a computer program. Something about AI “art” cheapens our understanding of what art is, just as IKEA cheapens our understanding of what furniture is, or what it could be— what it can represent about ourselves and our values. It’s just another iteration of the same consumptive culture, and at the same time, it’s also another example of the pragmatism that comes from the cheap facsimile of a thing. If IKEA furniture performs the function of being furniture just as well as something handcrafted, then what’s the “point” of getting the handcrafted thing? Again, we land somewhere intangible, irrational, illogical. We end up in the space of the ephemeral. The mass produced things technically perform just as well, but but but!— it’s on the tip of all of our tongues. Something is missing.

Modern culture seems to have a bottomless appetite for consumption, and what that brings to mind, for me, is that we are not satiated. We’re stuffing our faces with junk food and we’re never full. Whether it’s the IKEA furniture or the utter garbage on Netflix or AI “art”, we’ll consume it and carry on as though it doesn’t leave a bad taste in our mouths in any significant way. Perhaps it shows up when you look in the mirror and know you’ll never have that button, cartoon nose you have in those images. These technologies have an incredible capacity to create distortions in our perceptions of ourselves and our values. We’re not full, so we keep consuming.

Jake wrote:

“Is it impressive? I sure as hell can’t code for that, but it is just human intelligence from many other fields of work spread out in a really fast lookup table, (remember multiplication tables from elementary?) that enterprising tech-nerds call “artificial intelligence art.” Don’t let the computer scientists define art. And sure as hell don’t let them define intelligence. At the very least, let artists define it. Maybe it pisses you off that I am defiantly defining art here whilst simultaneously proclaiming I know how AI software works. Good. I pissed you off. That’s art. If an AI engineer gets to define art, I get to define what they have come up with as just a complex multiplication table. Pure poetry. Spending 5 bucks to get a computer to exploit your insecurities and give you the Marvel™ version of yourself is not art. It’s exploitation, and we are all clapping like happy little circus goers enjoying the fact that there are no more trees to turn into capital so they have turned us, our minds, images, insecurities, fantasies into capital for the machine.”

No One Forces Down Our Eyes

Zapata goes on to discuss the ways in which AI technology is not “just a tool” which is what many AI enthusiasts say to pacify the unconverted. He writes, “They want to sell the promise that someone with no experience can make the same image on day one that someone with years of experience can make. Based on their business model, the less need there is for an artist's intervention, the more successful and appealing their product is.”

Take this video below, which is coincidentally one of my favorite Pink Floyd songs, and the lyrical inspiration for all of the subheadings in this essay.

It’s an insanely cool video, and seeing it was the real nail-in-the-coffin that called me to try to understand my own feelings about AI “art”. I was awe-struck by this video, even as it all feels so fleeting. There’s so much detail but it’s hardly graspable, and it all plays into this disorienting, hypnotizing, hallucinogenic experience. It’s psychedelic, visually pleasing, exciting, and very effective for someone like me. It would be really hard for me to say that this isn’t “art” in its own way, and clearly the creator of the video benefited from AI (in this case, Stable Diffusion) as a “tool”.

As the song dips into a more frightening refrain (beginning at around 8 minutes), the images respond in kind with an unnerving self-awareness: images of machines; vast, impenetrable cities; circuit boards and other Blade Runner-esque imagery rapidly manifest and then dissipate on-screen. I asked the creator (an AI enthusiast, creating these videos to show people how beneficial AI is) if he chose that imagery on purpose. He said he did, or at least, he entered the prompts that would create the nightmarish imagery. It’s strange to me, that someone who believes that much in this technology would conjure those images at that part of the song.

“Conjure” is a bit of a euphemistic word, though. The problem arises for me particularly when, every so often, you can see a little flash of someone’s signature on the video, a mangled, illegible relic from the person who painstakingly learned the skills necessary to create the art that the AI unceremoniously heisted. The same can be said of the portraits. AI “art”, in this way, is just a more exploitative version of filters.

ChatBot told me, “even if AI systems were able to create original and appealing art, it is unlikely that many people would be willing to pay for it in the same way that they would pay for art created by a human artist. Art is often valued because of the connection to the artist, and without that connection, it is unlikely that people would be willing to pay the same amount for art created by AI.”

This may be true, and I would hope that people would spend more that $3.99 for a portrait from a real human artist who cannot be decontextualized from the economic system, but still, a lot of capital went toward an app company that is not accountable for where this art is coming from, and for what? A fad that was over in two seconds? And how long will psychedelic videos like this remain interesting, while something like Destino, created by Salvador Dali and Walt Disney, is psychedelic and timeless?

The direction we’re going ultimately feels a bit… cheap and sad. Doesn’t it? It’s not that it’s not cool or interesting in the general sense, it’s that real people would rather spend $25 a month to a corporation to essentially gawk at a litany of pretend pictures of themselves, than have a physical, tangible piece of artwork made by human hands especially for them? Yikes.

Call me a petulant pearl-clutcher if you must, but the reason we even felt the need to discuss this is because this is far from an isolated phenomena — in fact, it’s emblematic of the very structure of our consumer culture. You see it all around you if you know how to look for it: that “Thai food” even in Thailand isn’t traditional Thai food because people needed to cater to tourists’ precious palettes; the fact that everyone owns the same IKEA bookcase or Wal-Mart toaster oven or whatever; you get my point — it’s beyond monopoly. It’s the very fabric of the culture that exists around us. We consume the cheapened thing so often that we don’t even know that it’s cheap, and it only leaves us hungry for more.

Ecologically, this is known as “shifting baseline syndrome” but I think it’s worth extending the metaphor to society. Shifting baseline syndrome is defined as “a psychological and sociological phenomenon whereby each new human generation accepts as natural or normal the situation in which it was raised.” In reference to the landscape, this refers more to “lowering of people’s accepted norms for these environmental conditions,” with a sort of grotesque example being, when I was a kid I would see hundreds of dead deer on the road throughout the year, now I can’t remember the last time I’ve seen roadkill. Kids born today won’t be able to tell the difference, though. They don’t have a memory of a time when that was normal.

Ecology cannot be separated from society, however. We can see that we’ve accepted the suburbification of the world, turning farmland and ecosystems into strip malls and copy/paste middle-class houses, and that it doesn’t just impact wildlife or the ecological functioning of the world— it also impacts human perception of the world. Think of it this way: When I was a child, Amazon didn’t exist. If I wanted to do arts and crafts, I would go to Michaels, because that’s what was normal for me growing up. When my parents were kids, Michaels didn’t exist, so they would have to go find a local store owned and operated by a human being in their community to purchase art supplies from. They may have even had a human conversation whilst procuring their glues and whatever else. Nowadays, everything can be purchased on Amazon, so even stores like Michaels are at risk of becoming obsolete, and the human-scale retailer is all but completely dead and tossed haphazardly into a mass grave at this point in history.

Whether we are consciously aware of it or not, we’ve acquiesced to shifting baseline syndrome in uncountable ways in this age. If you don’t know that forests aren’t supposed to look like uniform collections of trees, you’ll think a collection of trees = a forest, even if what you’re looking at is a tree farm. If you don’t know what real Thai food tastes like, you’re not going to know that your pad see ew isn’t exactly a traditional dish at all until someone more knowledgable tells you otherwise. And if you don’t think AI generated images are threatening to art now, what will you think when kids grow up with it and can’t tell the difference between human and machine-made art? Will it matter to us then?

We need to understand that these technologies are already so much more advanced than we realize. If someone trained an AI to write erotica and tap into the long-distance trucker audiobook niche, they could make a fortune. It doesn’t matter if it’s good, and only really needs one human editor to go through and make sure it makes sense. In fact, I asked the AI to do just that, and I would fully believe that a human being wrote it! A cash-grabbing and lustful human, but a human nonetheless.

AI “art” is really just a cheap thrill — a cheapened, deadened version of the real thing, and it’s also eerily aware of our suspicion of it, which makes it even more disconcerting how rapidly it’s advancing. With so much content constantly melting our brains as it is, I shudder to imagine a world flooded with the truly flat, repetitive, and meaningless garbage that normalizing AI could bring.

Real art is often subversive, taboo, thought-provoking, and actually impactful. Jake pointed out the artistry of this scene from The Yes Men Save the World, where Jacques Servin and Igor Vamos trick and expose a bunch of crisis-profiteering assholes to buy into a phony apocalypse suit called a “Surviva-Ball” after Hurricane Katrina.

Jake said, “The Chinese artist, Ai Weiwei, has been imprisoned and tortured for pissing off the CCP. He was beaten so badly by police, for merely making art, that he needed brain surgery to reverse the brain hemorrhage. That’s fucking art.”

He went on to write:

“Remember when I talked about culture and narratives, and art as coming from a consciousness in said such culture? Well, M.F. Husain died in exile out of fear for his life from Hindu fundamentalists for drawing cultural figures in the nude. That’s fucking art.

Jafar Panahi is imprisoned in Iran and is banned from making movies. Not raping, not stealing, not killing, or abusing people— for movies, goddamn pixels on a screen. That’s fucking art!

Even the Nazi’s understood the power of art to subvert the masses and make people think. They knew it was so powerful that when the Third Reich rose to power they banned what they deemed “degenerative art.” Art was so powerful, it degraded the cultural narrative that supported Nazism. Because all culture is built upon stories, when the story of your culture is wrong, make fun of those stories like the many artists who had to flee Hitler’s Germany. Don’t let the bastards define art! Write books so goddamn good people want to burn them.

Banksy commissioned a performance of the nativity scene called the “Alternativity” to be performed at the wall between Israel and the West bank… that’s… fucking art. Your likeness looking like Chris Hemsworth or Idris Elba is Doritos™, not a 30 day dry-aged steak, reverse-seared, with the perfect crust.”

At the end of the day, we’re not bad people for not recognizing the shifting baseline syndromes that exist all around us. We’re susceptible to all sorts of cognitive distortions when change appears to be gradual enough, although I think it’s becoming more and more impossible to not notice the rapidity of the changing world. It’s a particularly challenging problem when the people who rail against these changes are maligned as “Cassandras” or anti-progressive “Luddites”, as I mentioned. It’s a great way to shut down actual human debate about things that actually matter, such as whether human-made art has a future in this stupid techno-topian society everyone seems so horny for. We do have a choice, however. We don’t need to be pressured to just get with the program if the program feels dumb and degrading. We have the choice to pay attention and start to notice these things, and to adjust our behavior accordingly.

No One Makes Me Close My Eyes

But, whether we like it or not, AI “art” is indeed here, so we may have to take a stance one way or another. We can’t just ignore it. This, like many other complex issues this project aims to discuss, will not be resolved by simple solutions. Instead, it’s incumbent upon us to change our minds about it. If we feed the demand, we only reinforce a world where artists are pushed to the margins, competing for pennies from machines and their “efficiencies”. Artistic expression is one of the most beautiful things about the human animal — are we really going to let it be suffocated by thieving, unthinking machines, and the unaccountable corporations at their helms, or are we going to try to scaffold and support one of the only things that makes this current iteration of human civilization even remotely tolerable?

Whether it’s poetry, portraits, music videos, screenplays, animations, or video games— these are aspects of human creativity that people don’t actually want to see subsumed by generic, uninspired, copycat machines. AI is not a tool in this sense: it’s a replacement mechanism. It’s here to make human beings redundant, just as industrialization deployed factories to make artisans redundant.

Even the AI admits it can “never replace human creativity or imagination,” but that doesn’t matter so long as we unquestioningly consume it. As long as there is a market for it, it will persist. As long as people don’t know shit from Shinola, it will persist. As long as people don’t respect the craft and all of the years of time, energy, and heart that is put into human made art and feel gluttonously satisfied by the junk-food version of art, it will persist.

Culture is a hard thing to challenge and to change. I wanted to buy those pictures, too (my broke-ness being the true instigator for me stopping in my tracks, not some moral superiority or something). The “Echoes” video is undeniably sick. It’s not that these things aren’t cool, it’s that we shouldn’t consume them unconsciously. We need to read the nutrition label and make educated decisions about our consumption choices. If you bought into the trend, I hope you do not read this essay as an attack and instead see it as it is intended: a call to consciousness. A call to awareness that we choose to feed the machine with our dollars, with our attention, and with our acquiescence to shifting baseline syndrome. And that we’re all susceptible to the tantalizing effect of cheap beauty.

AI can be a “tool” to create incredible and captivating works of art, as we can all plainly see in the Echoes video. But when the companies that supply the datasets are unaccountable, do not compensate or even notify artists that their work is being used, and infringe upon their rights as creators, it’s still an unethical enterprise. No matter the good intentions of the creator, he knowingly stole from other creators to make that video. Granted, he can’t monetize the video due to copyright laws from the music industry, so it does remain in a somewhat grey area. The portrait apps, on the other hand, have done their due diligence to make sure their illegal enterprise appears legal for all intents and purposes, such as in the case of OpenAI creating a nonprofit/for-profit hybrid model to ensure that the art is collected as part of a “public domain”, but then using it to make profits (a scheme they call “capped profit” whose checks and balances apparently leave them accountable to nobody but themselves).

“It’s not hard to imagine an ethical and consent-based generative AI image system, and that only makes it all the more galling that the ones being released now are emphatically not.” - Steven Zapata

The legal apparatus is most likely incapable of keeping up with something like this, but hopefully artists will try to demand legal protections in this case. What is more important, however, is that the culture changes and demands an artisanal class again. This is deep work that can’t happen overnight. Just as Charles Eisenstein wrote somewhere that “true community can’t be created so long as Wal-Mart exists”, art itself will not survive so long as we take artists for granted the way we have and allow them to be supplanted by machines.

Marques Brownlee ends his video on the topic on a pensive note, saying, “At the end of the day, if I’m being an optimist, which I try to be, I hope this makes us appreciate human created art more, but we gotta keep an eye on all these unanswered questions, and there are a lot of them.” There are a lot of questions. Does eating Doritos™ make us appreciate the flavor of homemade bread more? Does wearing scratchy, mass produced clothing make us long for a handmade wool sweater? Does seeing an artificial version of ourselves call us into consciousness about how we feel about our real selves? Maybe. Could it be true that the further we veer into the artificial, the more intense our longing for the real becomes? It could be.

I guess it’s just a matter of where we draw the lines, and when. What pushes someone over the edge, causing them to long for things that feel real?

Mary Harrington, in this article for UnHerd discussing AI writers in particular, has some optimism as well, writing, “I expect many creators to thrive anyway. It’s just that instead of trying to beat the machine at synthesizing the consensus, humans will be prized for their idiosyncratic curation of implicit, emotive, or outright forbidden meanings, amid the robot-generated wasteland of recycled platitudes.”

While we can’t expect this to go away on its own, and we have to start valuing humanness again as a practice, perhaps some good can come out of it. Perhaps it’ll be disruptive enough, or even boring enough, that we wake up to the lack of meaning all of this nonsense represents.

Harrington concludes her article triumphantly:

“If something remains distinctively the domain of human creators in this context, it’s not curating common knowledge but the hidden kind: the esoteric, the taboo, the implicit and the mischievous. The machine still can’t meme. May it never learn.”

Although I’ve tried to keep this essay light, with some sassy snarky-ness and self-deprecation, I hope to conclude this essay with the grief, which was masked by anger and frustration, that lead us to want to discuss this topic in the first place.

The machine, which doesn’t know love, or pain, or loss, or sorrow, is incapable of making art that fundamentally matters— and we all know the difference between art that matters and doesn’t. The machine will invariably add to the “content” creating noise that we’ve already been subjecting ourselves to, inscrutably, as long as I have been alive. I think AI “art” calls us to value, once again, the art that moves us and inspires us. As Jake said to me, it calls us into grief for all that the machine tries to take from us. “We can’t let the tech bros define art,” he said, tearfully. He was clearly moved and agitated the way that artists get before they are compelled to create. “We can’t let the machine steal art from us, too.”

He went into his closet-shaped office, feeling he’d reached the essence of what he was trying to say, and wrote:

“I recently began to teach myself guitar. I am not good, but for the first time in my life I feel like if I want to learn something I probably can. It’s a fun permission to give yourself. Will I be a professional musician? No, and that’s not the goal. Music has been integral to my life, as I am sure it is to yours. I don’t know anyone whose life isn’t saturated with music. It’s gotten me through the roughest periods, and helped me put testosterone, anger, and resentment somewhere that I had no place for in my teen years. Now, close to thirty years old, it helps me feel the full breadth of my emotions and experiences available to me as a human. I have thought for years of what a shame it would be if I never learned an instrument or felt like I actually understood music.

So far I have been doing a good ol’ job of monkey-see-monkey-do, learning “Blackbird” by The Beatles like the suburban 17-year-old girl I am.

The past week or so I have been trying to teach myself music theory. I want to actually know how music works. Scales, chords, etc. It has been a very rewarding experience to feel each individual piece click into place as I keep saying to myself “a-ha!” So that’s what that is, and that’s why that sounds good, and —holy crap— I can actually kind of invent something (albeit rudimentarily) that sounds a little nice.

I had spent a day earlier this week trying to write a whole piece about AI, which we were going to release in two parts: one Maren’s, one mine. My initial piece was full of anger and humor and all of the ideas you can expect to find here on Death in The Garden, and I thought what I had was okay, but it ultimately didn’t encapsulate how I actually felt, and I knew it on an intuitive level. “Ah, just forget it, baby,” I told Maren. “Just release yours— mine is crap.” I knew it was missing some undefinable essence— it, the art.

Until, earlier today, as I was plucking away on my guitar. I was experimenting with finding A chords in all the ways I could on the neck of the guitar, using a plucking pattern I had picked up from “Blackbird”. I became mesmerized by the simple, sweet, melancholic little tune that was summoned from my clumsy playing. In the next room, Maren was taking a bath while watching a TV show in preparation for the book club she is hosting soon for A Millennial’s Guide to Saving the World. She was watching the final episode of The Midnight Gospel by Duncan Trussell.

The first time we watched it together, the profundity of the scene made me weep. As I began to hear it in the background, my initial response was oh, god, I better shut the door, I don’t know if I can hear this right now. But the calm meditative state the plucking had put me into kept me rooted to my spot, continuing to play.

For those of you who haven’t seen it, the final episode of The Midnight Gospel is one of the most profound works of (in the truest sense of the word) art. Shortly before his mother’s death, Duncan interviewed her about her impending death from cancer. They had the most loving and beautiful conversation a parent and child can have about loving one another in the face of death. I tear up anytime I think about it, thus my resistance to hearing it. Sometimes you just aren’t in a place to go there. As my brain listened intently to the episode, imagining the animation I had seen over a year ago, and letting the notes float frictionlessly through my ears, I began to think about my father… and what his loss will be like. What regrets I have and which ones I can hope to abate with the time we have left. Will he truly know the love and gratitude I have for hm? Will he have felt loved and seen by me? Will he be able to express his regrets? Will I have done my job as a son well enough that my father can die in peace?

What those last conversations can be if we are so lucky to have them. When I think about losing my father the grief is so strong, I know not where to put the sensation. I can’t blame myself for often bypassing this experience. But in this moment, as the simple notes come through me, through the guitar, I began to cry. I imagined a moment to be able to share the sounds with a group of others, either as the player or merely a listener, as we all grieved for those we have lost or know we will. Even the simplest of sounds played with the least amount of skill made a space for those feelings to go. I was overcome by an immense desire to share this space with others, and to witness that space. It’s only so unfortunately rare that such a human thing comes over me.

There are many reasons to be angry about this AI “art” phenomenon. This piece is full of ideas and topics that Maren and I always ranting to each other about. (Most important to me is the reframing of the concept of “Luddite”. May it be my life's mission to make that cultural reframing come true.) But ultimately my anger comes from the mere defining of “art” by machines. Painting is a craft, and so is drawing, playing an instrument, dancing, standup comedy, writing, sculpture, etc, but all of these things can also become “art”. Art is so integral to who we are as humans, and so vital to understanding this confounding experience of life, that when I hear tech-bros telling me what they have created makes “art”, I get upset. The computer didn’t draw your face like a Marvel™ character so that it could understand the nuances of a mortal life. Nor could it create something that would open the cavern of my internal life like the simple sounds I was creating. Nor could any prompt entered into a piece of software come up with an image of my father that would connect the space between him and I like a hand-drawn illustration from myself.

Ultimately art is a purely human affair, an ephemeral, almost indescribable phenomenon that can only happen to a biological creature with a far too keen awareness of its own death, our loved ones’ deaths, the Earth’s death, and ultimately the death of everything. Our sapien sapiens-ness is so vast and immense, so unbearably heavy that there is nothing else to do but weep, draw, write, construct, and do what we can to create and channel a space for that understanding to flow— not only for ourselves, but for others, too. Let’s not muddy the waters of life any further than we have to. Let’s not sell that word for a quick buck. Art may be the most important and mysterious word we have. Let’s not give that up.

We have already let them take the word “intelligence”, do with it as they please, and create an industrial world from that description. Maybe one day we, too, can reclaim that word. But while we still can, let’s keep “art” archaic, primal, and as human as possible.

It feels like sometimes, it’s the only thing we have left.

Hmm. Art is expression through a medium. Technical perfection does not mean good art if there is no expression, no feeling, no soul.

So-called artificial intelligence (a marketing ploy: they are learning algorithms) is not conciousness. Roger Penrose explains this better than I ever could. Using AI just makes us stupid.

Looking forward to your views on "precision fermentation"!

As shitty as it feels for artists to have their work being stolen it does excite me to think about how AI will disrupt markets. I think the more disruption their is, the more that people will begin to wake up in all areas of life.