The Legacy of The Men Who "Pulled Bread from Air"

Hubris, Wizardry, and the Solicitude of the Future

If you would prefer to listen to the audio version of this essay, click play below to listen to a reading from our podcast:

“From the beginning, from the time when humans first tamed fire to the time they started growing grain, from the wings of Icarus to the artificial heart, humans have sought endlessly to cross nature’s boundaries, to break its limits, to make themselves more comfortable, more healthy, more powerful than nature alone could. This interplay between human aspiration and natural bounds has its own literature (from the myth of Prometheus and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to superhero comic books and mad-doctor movies) and its own field of play. I would call that field of play —the place in which humans can test their natural limits and often break them— science.” - Thomas Hager, The Alchemy of Air1

Stories bind us to our understanding of the universe and ourselves, offering warnings and prophecies, as well as key insights into the potentialities we may face. Whether we consider how daily we flit closer to the sun with our waxy wings, tinkering with AI, geoengineering, virtual reality, and robotics, we also find ourselves on other precipices of discovery, like that of fire, for which Prometheus was punished for eternity for sharing with us, or writing, which Thoth granted to the Egyptians despite King Thamus’ protestation that writing would undermine humanity’s capacity for memory. Our curiosity, as dangerous as Pandora’s, has been the key which has unlocked the world we see before us today: where anything can be delivered to anyone at the touch of finger upon glass, or even requested aloud to a resident robot; where I can read thoughts of anyone in the world at all times of day; and where I am sipping tea whose leaves come from tea plantations all over the world, all invisibilized and unknown to me. Like Faust, who so desired all of the knowledge of the world, or like Eve, tempted by the serpent to eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, humans have had the ability to make choices which ripple outwards from time in uncontrollable and unexpected directions. Our decisions have ramifications, as these myths and stories illustrate for us.

Humans have an incredible capacity for technology, invention, and mechanization, there is no doubt about that. But as billionaires and their hired scientists scheme for more and more control of nature, and their interests become more and more deranged from our own, we have to ask ourselves where we might draw the line. Which limits, or lines, will we refuse to cross? When is too far “too far”?

And furthermore, it might not be enough to merely dispense with the practice of breaking limits— in some instances, we need to attempt to return to a state of relative balance, if that is even possible. We ought to ask, from which breach of limits might we be able to return?

In this essay, I would like to ask this question specifically of one molecule, vital to the growth of plants, that until 1908, was trapped in the air— useless for our consumption. Making up 78% of the air we breathe, this molecule represented a resource in the Age of Industry, not yet tapped, which needed to be extracted. What happened when we harnessed this power? And how do we continue to be enslaved by its residual consequences today?

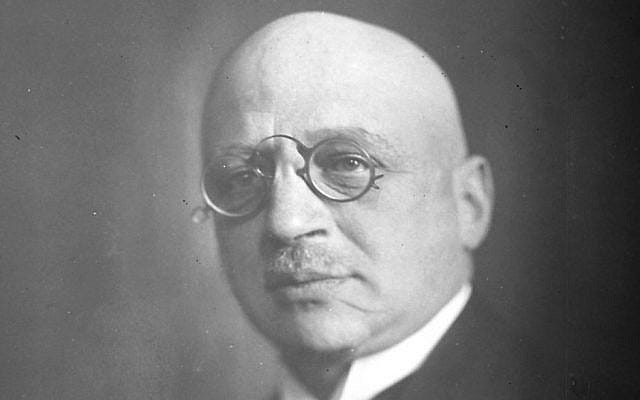

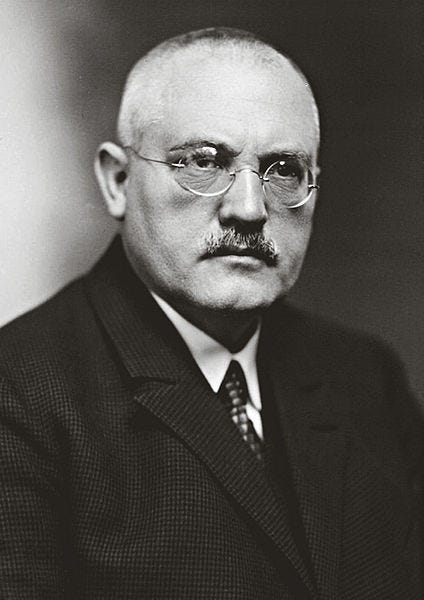

This story, like many others, cannot be disentangled from war, greed, and the intellectual limitations of Man. This story also defines every aspect of human existence today, albeit ambiently. As we cannot speak about modern agriculture without reckoning with an entire history of colonialism, genocide, and environmental destruction, we cannot talk about nitrogen without talking about the men who created the machines to harness it. One, a Jewish-born chemist, desperate to prove himself as worthy to the newly formed, scientifically progressive Germany. The other, a brilliant machinist and tycoon seeking riches in the industrial potential of the age.

Both would create inventions which would be responsible for the global population reaching nearly 8 billion today, and also, for the deaths of millions.

The First of Many Deaths

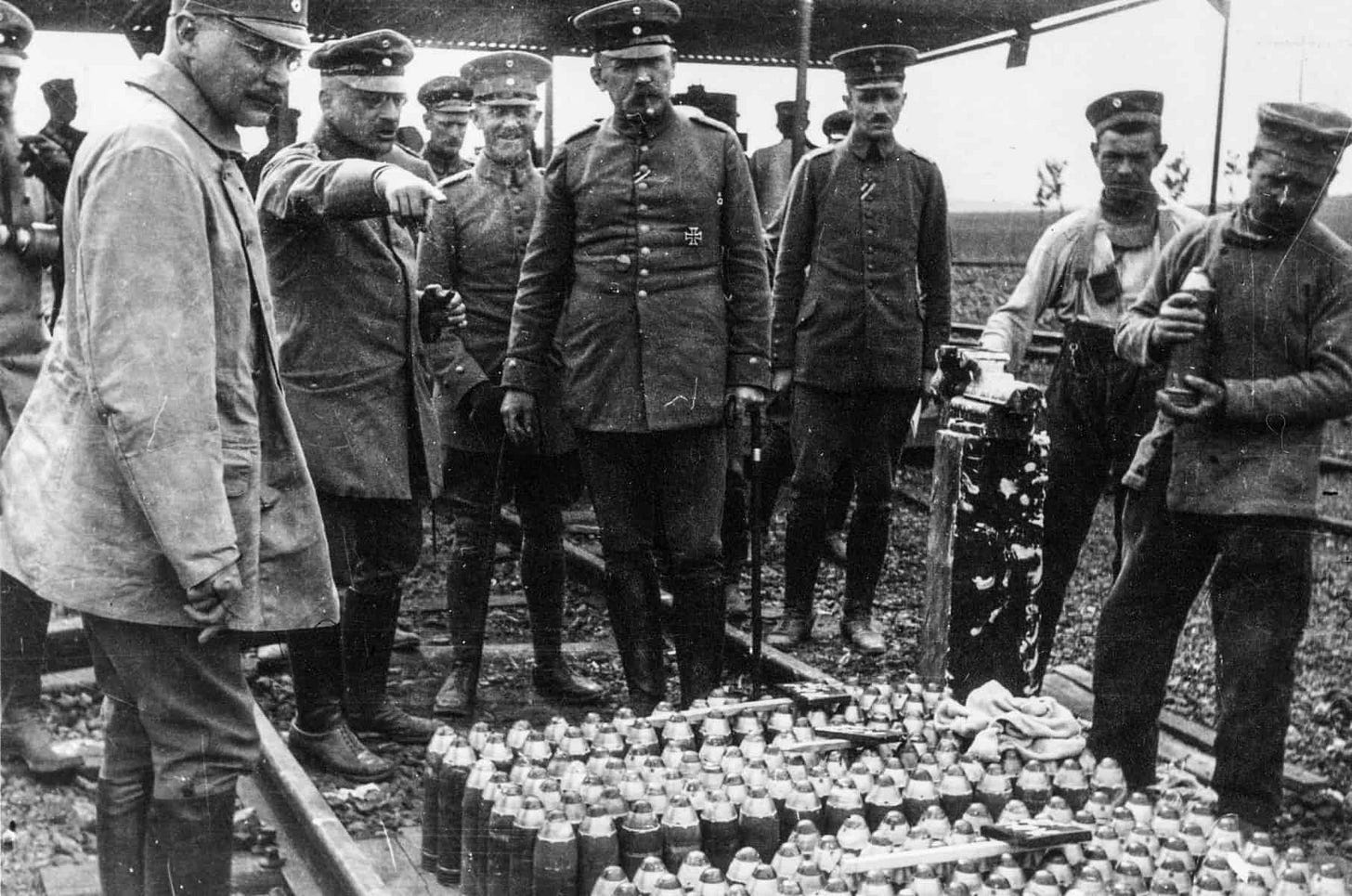

“The weatherman was right. It was a beautiful day, the sun was shining. Where there was grass, it was blazing green. We should have been going on a picnic, not doing what we were going to do…”2 It was Thursday, April 22nd, 1915. The German soldiers had been waiting for days, if not weeks, for the winds to change direction from northeast to southwest. Fritz Haber, the chemist in charge of Operation Disinfection, waited nervously for the perfect moment. The spring sun was cresting golden upon the lands, and for the moment, all was quiet. Suddenly, a shift in their favor. The winds were finally cooperating. They had to act quickly. Willi Siebert, a German soldier, wrote, “About supper time, the gas started toward the French; everything was stone quiet.” A wall of green-grey gas, four miles long, spilled over the lands, heavier than air, enveloping the land in a sickly fog.

“In less than a minute they started with the most rifle and machine gun fire that I had ever heard. Every field artillery gun, every machine gun, every rifle that the French had, must have been firing. I had never heard such a noise,” Siebert wrote. “The hail of bullets going over our heads was unbelievable, but it was not stopping the gas. The wind kept moving the gas towards the French lines. We heard the cows bawling, and the horses screaming. The French kept on shooting.” This monstrous fog of chlorine filled the trenches and the lungs of these young French soldiers, and they “fell to the ground convulsing, choking on their own phlegm, yellow mucus bubbling in their mouths, their skin turning blue from lack of oxygen.”3

"In about 15 minutes the gun fire started to quit. After a half hour, only occasional shots. Then everything was quiet again. In a while it had cleared and we walked past the empty gas bottles.

What we saw was total death. Nothing was alive.

All of the animals had come out of their holes to die. Dead rabbits, moles, and rats and mice were everywhere… When we got to the French lines, the trenches were empty, but in a half mile the bodies of French soldiers were everywhere. It was unbelievable. Then we saw there were some English. You could see where men had clawed at their faces, and throats, trying to get breath. Some had shot themselves.

The horses, still in the stables, cows, chickens, everything, all were dead. Everything, even the insects were dead.”

The Germans would ultimately squander their chance to make a significant advance on the French, and Fritz Haber’s rationalization that the gas would cause World War I to end more quickly, saving “countless lives,” would be moot.4

Regardless, the attack had been a small success for the Germans. Hundreds of Allied soldiers were dead, and the front line had shifted slightly in Germany’s favor. The Allies were quick to adapt to this new warfare, urinating on handkerchiefs and placing them over their mouth and nose at first sign of gas attack. Ultimately, the Germans would not win WWI, a fact which was unknown to Haber at the time of his victory party at his estate in Berlin, where he was fêted and honored for his loyalty to Prussia.

We may never know what Clara Haber said to her husband that very same night, before going out to the back garden and shooting herself in the chest. Her suicide notes were destroyed, probably by Haber himself, who, the very next day, was ordered back to the front lines to oversee the deployment of more chemical weapons against the Russians.

“I hear in my heart the words that the poor woman once said… I see her head emerging from between orders and telegrams, and I suffer.” Fritz Haber wrote shortly afterwards.

Her turmoil did not begin on April 22nd, 1915, but it did end on May 2nd. A famous chemist in her own right, Clara Haber, the first Jewish woman to be awarded a PhD in chemistry from a German university, had been cordoned to living miserably in the long shadow of her husband, who, 7 years prior, changed the world forever…

Thee, Boundless Nature, How Make Thee My Own?

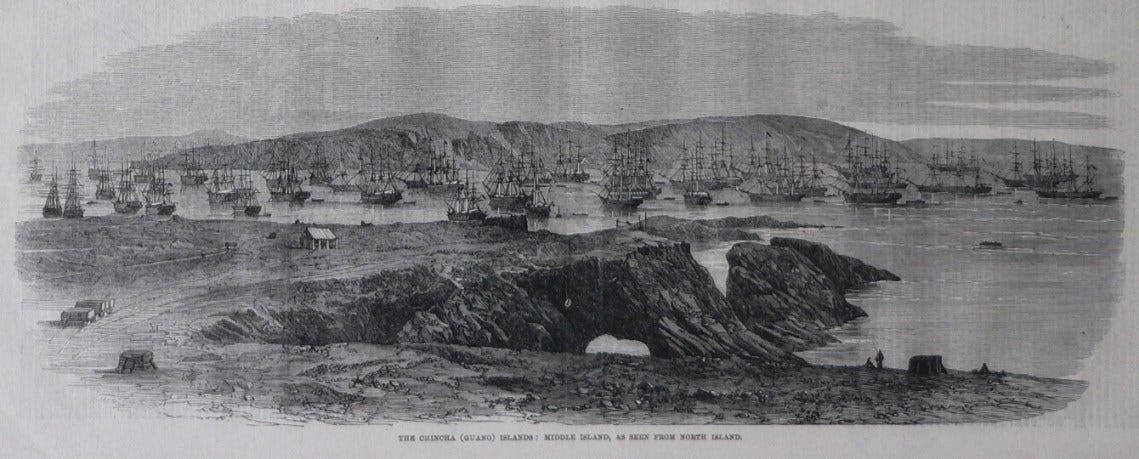

It took less than twenty years for 11 million tons of Chilean guano, which was as valuable as gold, to be completely used up. Europe’s desperation for fertilizers had even lead to tomb-raiding, using human bodies for fertilizer. With colonialism, Europe imposed this desperation in their colonies. Globally, this form of agriculture had already become dependent on other fertilizers, such as saltpeter and blood/bone meal, and Chilean guano represented the best-of-the-best during its short reign of dominance from the early 1840s to the late 1860s. It was so nitrogen rich that it had the potential to “burn” crops, much like when a dog urinates in the same spot of grass too frequently.

Slaves and coolies, "with rags tied around their heads and over their mouths" and their skins “white with dust” shoveled the guano endlessly, supplying ships which would wait in line at harbor for months on end to receive their load. The workers were malnourished, ill with “guano handling sickness,” exhausted, and horribly mistreated by their handlers/slavers.5 Rapa Nui, more commonly known as Easter Island, saw 1/3 of their population enslaved by pirates to work digging guano, which would lead to the utter decimation of their society. "By 1877, only 111 natives remained on Easter Island," writes Thomas Hager in his fascinating book, The Alchemy of Air.6

The guano was especially important to plantation owners in the United States, and its use kept cotton and tobacco fields producing, maintaining the enslavement of Africans— a continually lucrative business. Around the world, dependence on this magical substance was becoming more and more concretized. “Farmers, despite steadily rising prices, found it difficult to do without it.” Peruvian "white gold" was, for a time, the most important substance on Earth.

But by the end of the 1870s, the guano was gone. Luckily for the newly independent Peru and Chile, the Atacama Desert boasted an unusual resource, a unique mineral which could be refined into nitrate. Unluckily, this realization of the money that could be made led Peru (alongside Bolivia, in an alliance) and Chile into a war over the nitrate rich landscape. Chile would win the war, land-locking Bolivia, and soon, Chilean nitrate would dominate the world market. By 1900, Chile produced 2/3rds of all nitrate used on earth.7

The dependence on Chilean nitrates did not go unnoticed, and by the end of the 19th century, the incoming president in the British Academy of Sciences, Sir William Crookes, made a dire prediction in a music hall address in Bristol. “England and all civilized nations,” he said, “stand in deadly peril.” Following a Malthusian belief that population would outstrip food supply, Crookes solemnly warned his peers— something needed to be done. “It is through the laboratory that starvation may ultimately be turned into plenty.”

Germany, lacking sufficient colonies to exploit for farmland, was incredibly reliant on Chilean nitrates. If the country were to rise to prominence amongst its surrounding colonial powerhouses, it would need to figure out how to access the nitrogen in the air.

Though we breathe in and breathe out nitrogen all day long, we can’t use it for nourishment. Consumable nitrogen is known as “fixed” nitrogen, which comes from plants, specifically legumes, which have special bacteria in their roots which interact with soil biota to create fertility, otherwise nitrogen is released from the heat and pressure of a lightning strike. “The availability, or more commonly lack, of fixed nitrogen is so important that it serves as a cap on life on earth, a ‘limiting factor’ for plant systems (and hence for animals as well, since all animals depend in one way or another on plant eaters).”8 The call of the age was to break through this “limiting factor.”

Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, among others, responded to the call, but Haber and Bosch were the first to the finish line with machines capable of producing a commercial quantity. What is now known as the Haber-Bosch process refers to a chemical reaction which takes place when nitrogen (from the air) is combined with hydrogen (in the form of natural gas), as well as a catalyst, most commonly in the form of alloyed iron, is then heated to 400-500 degrees celsius and put under 200-400 atmospheres of pressure. This allows the nitrogen, which is a double bond, to split and join the hydrogen, creating ammonia. The ammonia turns to liquid when the gasses are cooled. From liquid ammonia, nitrogen fertilizer could be produced. Additionally, this process creates ammonium nitrate which can be used for bombs.

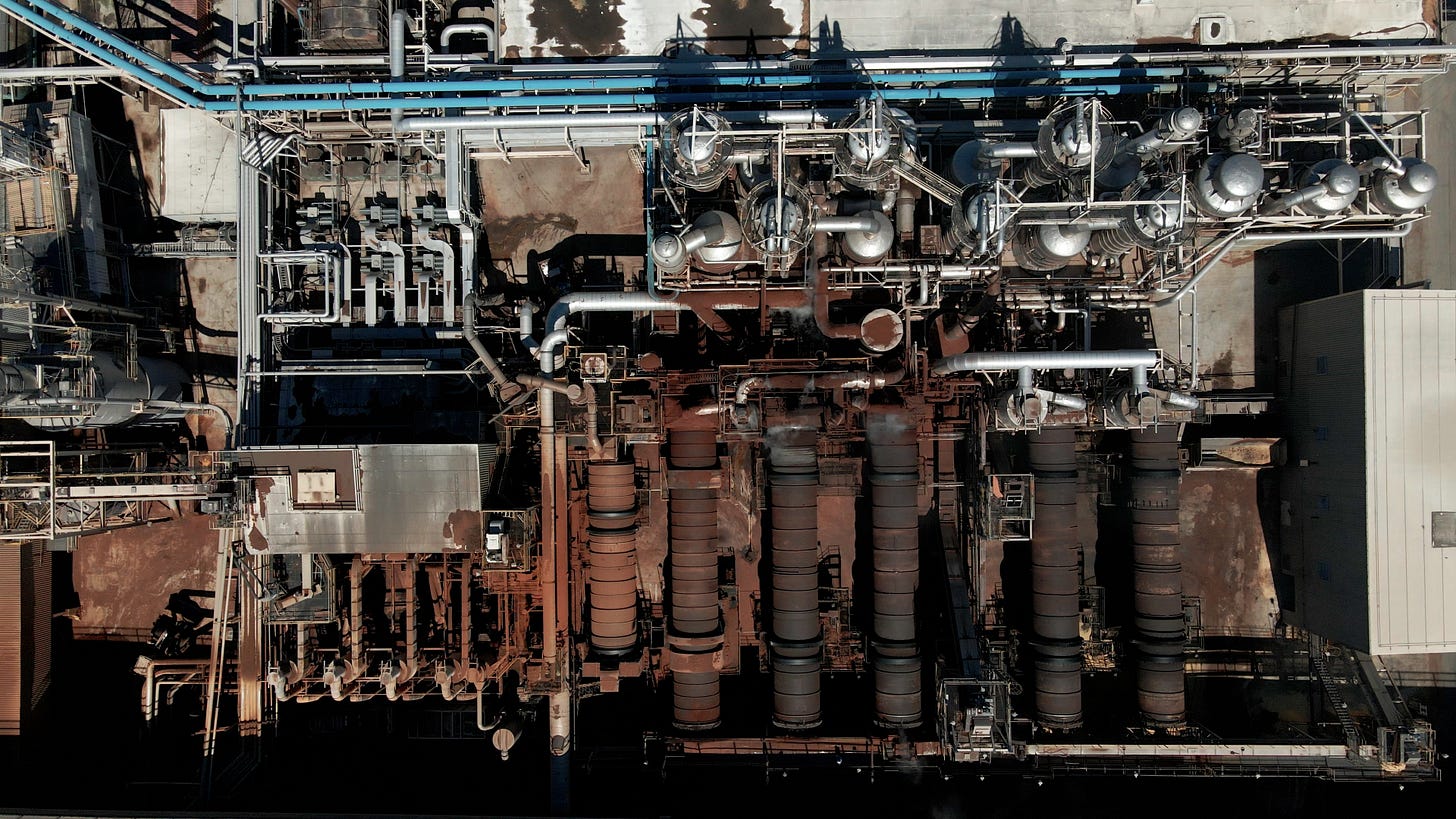

The process to create a machine that could handle these levels of pressure and heat was a long and arduous one. In 1908, at the time of the invention, nothing like it had ever been done before, but they did it. The first full-sized industrial ammonia plant was erected in Oppau in 1913. The success of the invention brought Haber and Bosch riches and fame, and though Haber would be shunned during his acceptance of the Nobel Prize for his chemical war crimes at Ypres, he nonetheless attained a fame that would carry him to his grave. He died around the same time as Nazism’s first percolations were bubbling in the war-ruined Germany in the aftermath of WWI.

The Haber-Bosch process is now responsible for around 40% of the calories consumed by humans today. The giant factories used to produce fertilizer "drink rivers of water, inhale oceans of air," and, astonishingly, "burn about 1% of all the earth’s energy."9 Doubling the available nitrogen has allowed for the human population to quadruple in 100 years, and with it, an even more interconnected global economy than the world has ever seen. Every nation, and nearly every human on earth is completely dependent upon the production of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer.

Today, we face what might turn out to be one of the worst food crises in human history. The conflagration of post-COVID economics, climate change, the war between Ukraine (and the West), and Russia, global supply chain issues, and the farmers protests in India, the Netherlands, and Ireland herald a new era of geo/sociopolitical chaos, in which governments are coming head-to-head with ecological and social limits. These examples are only a few among many. On top of this, the earth has never been in a more ecologically tenuous position, as water and nutrient cycles worldwide have been all but destroyed under this economic model that promotes growth and extraction at all costs. Globalization and crony capitalism have created an interconnected and nearly incomprehensible system of trade where one person’s famine is another’s fortune. And without the Haber-Bosch process, none of it would be possible.

Masters and Possessors of Nature

“While science itself is a product of social forces, and has a social agenda determined by those who can mobilize scientific production, in contemporary times scientific activity has been assigned a privileged epistemological position of being socially and politically neutral. Thus science takes on a dual character. It offers technological fixes for social and political problems, but delinks itself from the new social and political problems it creates.” - Vandana Shiva, The Violence of the Green Revolution10

The chlorine gas which filled the trenches at Ypres, and the laboratories created by Haber, would eventually be used to create Zyklon-B, the pesticide used in concentration camp gas chambers. Though Haber converted to Christianity, many of his Jewish relatives would perish from the chemical during the Holocaust. Haber would be dead before this happened, escaping the turmoil of knowing his inventions would be used to massacre his own people: his partner, Carl Bosch, would not be so lucky.

“Bosch’s life work, his breakthroughs and factories, his attempts to feed the world and make profits for his company, were being used to arm and fuel the Nazi machine,”11 writes Hager. Carl Bosch was anti-Nazi, standing up for his Jewish workers when the regime started instituting discrimination into law. He was asked to deliver a speech in Munich, which would require a “Nazi salute and the requisite words of tribute to Hitler.” He tried to get out of it. When he couldn’t, he showed up drunk and only mentioned Hitler once, in a “derogatory” way. He was not arrested, but henceforth, his world became very small— living under the weight of the reality that his machines were being used to fuel a monster.

His factory at Leuna would become the single most important strategic target of WWII, as the plant had been converted from ammonia fertilizers to producing synthetic gasoline, as well as bombs from ammonium nitrate. It was the most heavily defended piece of land in all of Europe during the war. Bosch would die before the plant, called “Flak Hell” by the Americans, was finally, after years of attempts and casualties, systematically destroyed by the US Air Force.

Neither would live to see that this Nobel Prize winning, revolutionary scientific advancement would inadvertently create the most entangled web of catastrophic issues the world has ever seen. For when Haber and Bosch “pulled bread from air” they set in motion a trajectory for humanity that seemingly can’t be undone. Together, they released a genie from the bottle, an idea made manifest in reality that the limits imposed by the natural world could (and should) be broken under the right conditions of heat and pressure, but as we all know, the Haber-Bosch process was only the beginning.

In his outstanding 2018 book, The Wizard and the Prophet,12 Charles C. Mann explores the two conflicting ideologies of modern environmentalism. The Wizards, as Mann calls them, are the technotopians— those who believe the solution to the worlds problems exist in data, equations, and ultimately, in technological advancement. Unbeknownst to most of us, the Wizards are infiltrating our food system (and every other system), with the implicit belief that the world should be tinkered with by Man to suit our needs. According to Mann, this all started in the early years of the 20th century, spearheaded by one man from Iowa.

Norman Borlaug would be only a little over a year old when Operation Disinfection was unleashed across the Atlantic, yet the series of events that followed, most importantly the economic fallout of WWI and the Great Depression, would set him on the trajectory that would lead him, too, to a Nobel Prize.

During the First World War, the United States government incentivized farmers to increase their dairy herds and invest in new infrastructure like tractors and milking machines to send milk to the troops.13 Farmers were paid handsomely for their contributions, but when the war was over, they quickly realized the debt they had been saddled with and the government, in horrific recession, offered no respite. Demand for milk fell along with prices and “milk producers were selling every gallon at a loss.” Foreclosures on farms ramped up, and dispossessed families flocked to cities for work.

Borlaug was 19 years old when he witnessed first-hand the devastation of the Great Depression in Minneapolis, and experienced the hunger-induced violence that up-swelled from the desperation of these farmers who had lost everything. A protest of famished men, women, and children erupted in front of him:

“… the guards rushed the protestors, bringing their clubs down in a coordinated attack. Cries of pain rose as bloodied men collapsed. Others grabbed at the milk canisters in the trucks, pulling them to the ground, splashing milk on the cobblestones. Borlaug was terrified. Abruptly the milk trucks lurched forward, into the melee; people fell back shouting, a panicky shuffle pinned Borlaug against a factory wall… When the crush eased, he ran shaking through the fight to his boardinghouse. The wounded were lying untended on the ground.”14

This was the moment when he decided that something needed to be done. Hunger lead to chaos.

The career that would follow this moment would be borne of very good intentions— the idea that “food is the moral right of all who are born into this world.” As he found himself among some of the most technologically advanced agroniminist minds of his time, Borlaug started to view the issues beleaguering agriculture as problems to be solved with technology and innovative tools; viewing agriculture from a lens of “plant pathology” rather than ecologically. His first foray into the world of artificial selection and plant genetics involved the problem of stem rust, a fungus that was affecting wheat plants worldwide. Through painstaking breeding work and a financial relationship with the Rockefeller Foundation, he was eventually able to breed wheat that could withstand the fungus. Then he selected for traits that would produce the best bread. Then he selected for traits that would produce the most seed, but the plants were too tall and suffered from lodging, which is when the seed head becomes too heavy to be supported by stem, and the plant falls over. Over many seasons of breeding, he managed to breed a “dwarf” wheat plant (resistant to lodging), with high yields, quality flavor, and that was resistant to stem rust. These seeds, marvels of human ingenuity they were, would be sold as a package to farmers with fertilizers, pesticides, and prescriptions for irrigation, which would change the trajectory of agriculture forever.15

Of course, artificial selection had been occurring since the dawn of agriculture, so that wasn’t new. What was new was this idea of efficiency, that agriculture was problematic because plants weren’t growing to the potential made available by fertilizers, and that scientists held the key to unlocking that potential.

The Green Revolution spread across the globe, and with it the normalization of “package” deals for seed varieties which promised high yields to farmers. First it was wheat, then it was maize, and then it was rice— all genetically and precisely developed to be the most resistant to disease, pests, and fungi.16 “The Borlaug package has become an emblem of the view that the road through humankind’s environmental difficulties lies through the groves of scientifically guided productivity,” writes Mann.17 Anything that advocated against this limit-busting was seen as backwards, unprogressive, and “unscientific.” The seeds of a Wizardly worldview had been planted into the fertile industrial soil.

While these innovations have certainly seen a rise in yields, what started as an altruistic goal quickly, in the matter of decades, devolved into the greatest consolidation of wealth and power the world has ever seen.

In her book, The Violence of The Green Revolution, Vandana Shiva explains the impetus for the Green Revolution being spread through India (and other parts of the world): colonialism.

Colonialism separated people from their lands, subsistence livelihoods, and entrenched them in the cash crop commodity system we see today. Over decades of colonial rule, the sustainable agriculture system that India (and Mexico, where Borlaug worked with stem rust) had since the beginning of the Indus Valley civilization was all but lost. Norman Borlaug was instrumental in the Green Revolution in India, and again, he did it for all of the right reasons, but the question of why these new practices were necessary never emerged. What ended up following the Green Revolution in India, and Borlaug’s Nobel Prize, was the consolidation of more lands into fewer hands, the displacement of farming communities, shunting people into cities.18

On top of that, the excessive use of fertilizers proved perilous for the land, a land which had been maintained through nutrient recycling and careful management for generations:

“Twenty years of Green Revolution agriculture, have succeeded in destroying the fertility of Punjab soils which had been maintained over generations for centuries and could have been indefinitely maintained if international experts and their Indian followers had not mistakenly believed that their technologies could substitute land, and chemicals could replace the organic fertility of soils… the nutrient cycle, in which nutrients are produced by the soil through plants, and returned to the soil as organic matter is thus replaced by linear non-renewable flows of phosphorus and potash derived from geological deposits, and nitrogen derived from petroleum.” — Vandana Shiva, The Violence of the Green Revolution19

The idea of “inputs” being a necessary component of agriculture was concretized during the Green Revolution. Little by little, all around the world, resources started being extracted, and a globalized, interconnected agricultural economy began taking shape. No longer would fertility stay locked in place, subject to limits. With Borlaug’s seed-fertilizer package, farmers became but one leg of a massive centipede-like machine spanning across the globe. NPK (for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, all necessary nutrients for plant-growth and maintenance) fertilizer now became a global enterprise. Rather than utilizing the fertility of the landscape and the animals on it, a farmer would need, say, potash from Russia or southern Utah, phosphorus from the Sahara Desert or China, and nitrogen from Canada or Germany.

The Green Revolution helped supply chains become a lot more complicated, and as it got more complicated, it became more pervious to consolidation by the biggest, the most powerful, and the wealthiest in the Ag Game.

You Will Not Wrest From Her With Levers and With Screws

In the early 20th century, nature was a problem to be solved, and humans finally had the tools to solve it. Unlocking the potential of nitrogen was merely the first step in man’s quest towards domination over natural systems— our first real inclination that we could wield the invisible forces of nature for our own benefit, ordering and “improving” the process of life. Thanks to Norman Borlaug, we created crops that bent to our will, so long as they were fed the right cocktail of fertilizers and agrochemicals. What we didn’t expect were so many unintended ramifications.

“We know only that Haber-Bosch has altered these cycles enormously by injecting the world with a gigantic dose of synthetic nitrogen. It is as if we made our planet the subject of an experiment, doubling its food to see what would happen.” — Thomas Hager, The Alchemy of Air

One thing that we know has been a result of this surplus of nitrogen is that half of it ends up in the air and water, not in our food. This leftover nitrogen is what is feeding the algae blooms in the Dead Zone off the coast of Louisiana in the United States, the 23,000 square mile Dead Zone in the Bay of Bengal20 as well as feeding the toxicity of the Baltic Sea, one of the most polluted marine ecosystems in the world21. This eutrophication is happening all over the world, choking out ecosystems as opportunistic plants, such as algae, proliferate from the excess nutrients.

Nitrogen run-off happens mostly as a result of over-fertilization, but it’s also in this abundance of nutrients that confined animal feeding operations became possible, which also invariably causes nitrogen run-off. Because it became possible for grain agriculture to become so prosperous, processed foods came into vogue. The surplus of biomass from these industrially produced plant-foods represented a waste problem, unless they could up-cycle it, which they did, in livestock (around 85% of livestock feed comes from used hulls, stalks, meals, and other inedible agricultural byproducts)22. Because of this, manure rich in nitrogen from factory farms also causes nitrogen pollution, which is why the Netherlands has unleashed a plan to outright eliminate much of the country’s animal agriculture sector.

In the United States, “manure management” accounts for 5% of nitrous oxide emissions, whereas “agricultural soil management” accounts for 74%23. What this really means is that metric tons of fertilizer are not absorbed into the plant or the soil, to great expense financially, and more importantly, ecologically. It makes sense to want to curtail these emissions in the Netherlands, but the method, as evidenced by the response to it, is not popular at all. Cattle farmers took to the streets to protest the “unrealistic” goals to reduce nitrogen emissions by 50% by 2030, a move, which, at first glance, may seem “anti-nature.” But when you consider the plan’s explicit exemption for construction and development, it’s more understandable why farmers would be angry about the hypocrisy of their sector being targeted while other nitrous oxide emitting industries get a free pass. They feel scapegoated in a time when farmers using “circular” agriculture can be part of the solution to waste management.

Natasja Oerlemans, head of agriculture for the World Wildlife Fund–Netherlands and spokesperson for this plan, says that in order for the Netherlands to promote and scaffold “circular agriculture,” the Netherlands would have 50% fewer animals. What she also said, (in an interview which has since been deleted from YouTube), is that “soy is coming to the Netherlands to feed animals… these are feedstock that can easily be used directly by humans to eat.” She went on to say that, “we need to feed the world in such a way that we use land efficiently.”

Needless to say, with this sort of narrative being part of the greater plan, many people can’t help but to scrutinize the connection between Holland’s Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, and the World Economic Forum, which is deeply intrenched in investments for fake-meats and other plant-based food alternatives.

Rutte says, “The Netherlands is committed to forming partnerships that will catalyze the innovations that are needed to address the food system challenges.” These “innovations” are primarily in the form of expanding plant agriculture, but using “geospatial tech” and “precision farming” — high-tech solutions that the elites have long been peddling, next in the latest necessary efficiencies required for agricultural development and supposedly mitigating nitrogen pollution.

The Netherlands is far from alone in this sort of scheming. In fact, last month, the USDA awarded $3 billion to a “Climate-Smart Commodities Program.” So, what are these technological advancements and why do they matter? They seem innocuous enough. (What could be so terrible about “climate-smart” agriculture?) They matter because this is yet another round of the same story, which is being used to further entrench the world in the industrial food system and all of the supply chain precarities that follow it. There is a wholesale transformation occurring, and most people don’t even know about it.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution24 is indeed upon us, and within the food system, it fundamentally centers around data collection, AI, augmented reality (I can’t be the only one who has seen the Meta commercials for AR agriculture, right?), drones, satellites, producing so-called alternative proteins (including cell-cultured meats and 3D printing food), and genomic editing. The assumption of the Fourth Industrial Revolution is that the world will continue to be hyper-connected with the internet-of-things and increasingly digitized, and therefore all aspects of society must follow suit. The premise it is based upon is a world increasingly blended with technology and inculcated with progressive machinery.

The consolidation of the industrial food system is old news, though it’s worth mentioning certain figures, such as Bayer (which merged with Monsanto in 2018) controlling 23% of the world’s market for seeds, or that 4 firms control 62% of the world’s agrochemical market. What is less known, or perhaps less understood, is that this move into data and tech is far less about “feeding the world” or even improving agriculture— it’s about accessing new markets.25

“Before, we sold pesticides, seeds and fertilizer. Now we’re a farm services company – we sell service and technology...selling individual products, we had hit the ceiling, there was no more room.”

- Mao Feng, chief brand manager for Syngenta Group’s MAP

A recent report by the ETC Group, titled Food Barons, lays out the extent of the “Wizardly” acquisition of agriculture. Would Norman Borlaug rejoice at seeing the technological advancements in agriculture today? CRISPR technology is being applied to not only plants, but livestock, insects, and microbes. The “package” deals of irrigation, fertilizers, and pesticides are merely a memory of yesteryear. Now, “instead of limiting sales to seed plus a linked-herbicide (Round-up Ready corn seed and Roundup, for example), seed/pesticide firms are now selling (the promise of) high-yielding, weed-free, bug-free fields” with “data-driven input recommendations” by in-house agronomists or machine-learning, “modeling of potential profits based on predicted weather plus the application of additional proprietary products, soil sampling via in-field sensors and field-scouting via drone on a fee-per-pass basis.”26 The idea is to integrate all aspects of the farm under not only the banner of one company, such as Bayer, who owns the seeds, the agrochemicals, the tech, and increasingly, the data, but to control every aspect of the operation through vertical (and virtual) integration. Just as Big Data is farming us for our preferential data, Big Data aims to farm farmers for their agricultural data by offering them unprecedented “efficiency” through these technopackages.

“The justifications for using Big Data to advance and ultimately realize “precision agriculture” are already familiar and vary little from the arguments pushing for the acceptance of GMOs more than a generation ago: we are told that food production is inefficient, unpredictable and imprecise and so we must leverage newly-available technologies to produce more food more reliably (i.e., increase yields) for a growing global population – without increasing the need for land and while reducing negative environmental impacts from agriculture.”27

But perhaps Borlaug would have reached his limits as well. It’s one thing to do artificial selection, but surely it’s an entirely different thing to develop gene-editing sprayable pesticides? RNAi is a technology meant to kill pests using “gene-silencing” technology, meaning the pesticides are designed to switch off genes which are essential for the organism’s (i.e. insect’s) survival. In other words, “the technology is designed to modify organisms in the open environment.”28 Additionally, they plan to genetically modify plants to have this gene-silencing capacity to deploy during predation. And we thought regular ol’ GMOs were scary.

If it’s not terrifying enough that this is being developed at all, a study published by Monsanto (now Bayer) in 2018 “found that its genetically engineered corn equipped with RNAi to kill the Western corn rootworm also killed non-target beetles in laboratory experiments.” What could go wrong?

All of these advancements are lauded as totally positive— especially “climate-positive.” Fertilizer companies are capitalizing on climate fears by promoting “green” ammonia (which uses renewable energy for electrolysis) or “blue” ammonia, which uses carbon capture technology.29 Additionally, much of the data being mined will be used to calculate carbon credits, using what sort of methodology, and sold to whom exactly? Nobody knows. On top of that, these Big Agribusiness firms are using blockchain to “improve trustability” amongst consumers, a way to counter the “irrational preferences” (to quote Stan Dotson, multi-decade advisor for Monsanto and VP of Digital Strategy and Transformation at Bayer) who want food “free-from-everything.” ETC Group writes that this is the Food Barons response to the “buy-local, know-your-farmer trends.”30

As in the case of the Climate-Smart Commodities Program, it’s impossible to ignore the amount of Big Agribusiness players that received grants from the U.S. government, including Cargill, the single largest commodities trader on Earth. What that money will be used for (and how much was granted) is a mystery as of right now. Some grant money went to places that are well deserving, such as tribal organizations or Black farmer groups. But what should be clear is that rather than investing all $3 billion into local food systems, regenerative agriculture, agroecology, community gardens, or permaculture projects, they are investing a very significant portion into the maintenance of the industrial food system (with a pinch of “green”), all while partnering with carbon creditors, tech firms, and massively destructive corporations (PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, Nestle, Tyson, Walmart, and our friend Bayer, to name only a few).

This recent episode of Tech Won’t Save Us with an ETC Group researcher, Jim Thomas, offers an incredible breakdown into the industrial food system and the ways in which Big Tech and Big Data are increasingly encroaching on our lives.

Some will argue that the transformation must occur in the industrial sector, as it’s the most damaging ecologically and socially, but should corporations worth billions of dollars receive money to do the bare-minimum, like using compost or no-till drills, or would that money be better put to use by small-scale farmer groups? Needless to say, this shit is sobering.

While Still Man Strives, Still He Must Err

It would have been impossible to foresee the global economy being shaped by these inventions. The industrial age of food has been a relatively recent phenomena, only spanning a little over 100 years. The confluence of commodities trading amongst nations informed the main agricultural practices, which slowly homogenized food production over time to a handful of grain staples that can only be grown in this industrial manner, and which strives to exclude all other kinds of food production, whether it be agroecology or regenerative agriculture.

Sir William Crookes, during his address in Bristol said, “Before we are in the grip of actual dearth, the chemist will step in and postpone the day of famine to so distant a period that we and our sons and grandsons may legitimately live without undue solicitude for the future.”

Have we finally reached that “day of famine”?

The excess of nitrogen raining from the air, in the water, and in the soil are now ravaging ecosystems worldwide. The homogenization of plant species and the cycles of debt which have ensnared farmers expose incredible vulnerabilities. Land has been stolen and enclosed upon, and our fates seem more entrenched in the whims of the corporatocracy than ever. We have sucked the fertility from the soils, destroyed the water cycles, and swallowed all the fecundity the earth offered to us in the acquisition of this type of totalitarian agriculture. Because these soils are dead and denuded of nutrients, agricultural production is nearly entirely dependent on this process, and it cannot be easily reversed. We have ceded our sovereignty of the land and the food produced on it to a handful of titanic multinationals.

The sons and grandsons of those fancy men in that Bristol music hall might have lived without “undue solicitude for the future”— not us, however. Not the great grandchildren, or great great grandchildren. The invention, meant to stave off starvation, based primarily on an incongruous belief that human population growth grows exponentially without any reason, unique and unlike anything else on earth, has led us into a very dark time in the human story. The belief that we are inherently not subject to the balances and limitations of the living world has led us to a precipice— upon which we must tread ever so lightly.

What is also important to recognize is all of these innovations were the products of states of emergency — the urgent need to avoid famine lead to the Haber-Bosch process, the urgent need to, again, avoid famine lead to the Green Revolution, and now, the urgent need to avoid famine is ushering in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, precision farming, augmented reality, high-tech machinery, and even more specialized seeds with specialized agrochemicals controlled by even fewer Big Agribusiness multinationals. Avoiding famine is a good goal, but are we even remotely thinking about it correctly?

Meanwhile, 70% of the food on earth is still produced by small-scale peasant farmers. What is threatening the food security that these peasant farmers represent is not “inefficiencies” in agriculture— its the consolidation of the food system and the enclosure of lands and seeds. It’s the imposition of high-tech debt-saddling. It’s the globalized food system which focuses on the production of calories over the production of real food, and insists on exporting those calories around the world rather than keeping them in place. As mentioned in the Food Barons report, “The reach of digital food and [agriculture] is rapidly expanding to peasant and smallholder agriculture in the Global South. Digital technologies offer new forms of control and value extraction that threaten to further usurp farmer autonomy and decision making while facilitating and expediting a new era of land grabbing.”31 AGRA, which is the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s pilot for a Green Revolution in Africa, represents the “philanthropic” arm of the industrial agriculture land-grabbing apparatus. Watchdog and activist groups like AGRA Watch (which call this sort of philanthropism “biopiracy”) and Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa are dedicated to monitoring and resisting these encroachments. The original Green Revolution was a product of colonialism, imperialism, and the disruption of place-based agriculture systems, heirloom seed varieties, biodiversity, and self-determination. What is different today?

This food crisis is a food price crisis. The industrial food system is rigged to benefit the big players, and it abhors the local. It abhors the human scale agriculture that exists all around the world, the system which actually feeds people — the system that is gravely under threat.

The IPES released a report earlier this year, stating that “the world’s poorest countries and populations remain critically dependent on imports of staple foods from a handful of exporting countries and corporations.”32 They recommend nations work to "rebuild domestic food production" stating "it will be crucial for all regions to rebuild more diverse production and trade systems, grounded in local and regional territories."33 This is essentially the antithesis to the direction the Food Barons would have us go.

They emphasize: “Agroecology is a form of crisis response, a route to resilience, and a low-cost way to hedge against various shocks – making the shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems more urgent than ever.”34 Responding to food emergency through resilience, community, and renewable systems is very different than responding to emergency with brash technological advancements. Unfortunately, certain public figures are opportunistically pointing to Sri Lanka's recent crisis as "proof" that organic farming or agroecology are not solutions and are part of a backwards ideology. The reality is, what happened in Sri Lanka was incredibly complex and mainly a result of an inept government that didn't listen to farmers. Agroecology and regenerative agriculture do not magically manifest overnight— it takes time, and time was not given to the Sri Lankan farmers to transition. Reducing dependence on the industrial machine is a way to start building resilient, local systems that can actually withstand food crises and climate variability.

Still, upon reading the IPES appraisal of the Netherlands’ “ambitious buy-out schemes” for “managed reductions in livestock numbers,”35 I fear a terribly important opportunity is being missed— one which puts animals and land back at the center of our food ways. Animal husbandry not only inoculates landscapes with fertility, but it also provides meaningful lifeways, resilient, nutrient-dense food sources, and the ability for transhumance, which will be needed as the climate changes. As I mentioned in my previous essay, pastoralism can represent an invaluable form of food security for local communities. If bread is inaccessible in Norway or Sweden, there are reindeer. If maize is inaccessible in Tanzania, there are cattle. The problem is how we manage these animals— and many of the reasons for this mismanagement come from a colonial dispossession of land, which, yes, can be reversed and halted creatively and justly, in collaboration with local people. The grazing of goats, sheep, and cattle by regenerative farmers and pastoralists alike does miraculous things for the landscape, but in order to have the full impact, certain lands need to be returned to grazing. As Vandana Shiva wrote, “To regenerate living soil, we need regenerators.” Regeneration cannot happen in small pockets of beautifully managed and privately owned land— it has to happen everywhere. Unfortunately, some of the most degraded lands on earth are the lands most exploited by the Haber-Bosch process and Borlaug packages. These monocultural lands have been biotically cleansed and pumped full of chemicals for so long that they are barely hanging on.

This is not to say that this would be an easy process: regeneration, I’ve learned, is multilayered. Bioregions are interconnected socially as well as ecologically. If your neighbor sprays a toxic pesticide on their field, your land is contaminated as well. Likewise, if your neighbor is suffering, is your land really regenerative? If your neighbor refuses to participate in your creative experimentation, such as running goats through their forests, or sheep on their pastures, yards, and ski slopes as we’ve seen at Fjällbete, then relationships need to be regenerated as well.

The point is, it’s possible. We’ve seen it. We’ve seen people be creative and considerate and look at the whole ecosystem (the people included), asking, how might I serve this land? Conservationists around the world agree on the importance of grazing and of people in the landscape. What needs to change is our minds.

Which is why regeneration is also psychological: we have to question the narratives we are being presented. Is it really so simple that the Netherlands moving away from animal agriculture is a good thing? Do we have to take the industrial food system for granted? Should Klaus Schwab and the rest of the world’s elites have the majority of decision making power over the food system? Do we want this for our future?

Have We Ceased to Understand the World?

The intentions behind any advance in technology have usually been good. The person who planted the first einkorn seeds in the floodplain of the Euphrates couldn’t have known that 12,000 years later the world would be on the edge of collapse because of an economic system that was borne from those first accumulations of grain. Fritz Haber only wanted to be a good scientist, and a good patriot. He couldn’t have known that his invention would lead to such a profound dependence, increasing inequities around the world, vicious and unrelenting cycles of debt, and the eutrophication of the land. Norman Borlaug just wanted people to be fed — he wanted peace.

In the brilliant book, When We Cease to Understand the World, author Benjamín Labatut breaks down these scientific unintended consequences, and the madness of the men who unleashed them upon the world. What does it mean to be the man who opened Pandora’s box? What does it mean to break through a naturally (and wisely) imposed limit, unleashing unknown terrors upon the world?

Above is an interesting video on the subject of Fritz Haber. It was recommended to me by a handful of people and it does a fantastic job of breaking down the story of this man and his invention (with wonderful animations), but watch for an eerie omission at the end by the creator. The verbiage used, to me, points to a very specific way of seeing the world, one which, I believe, lies at the center of the epistemology which the ancients were warning us against, and which has got us into this mess in the first place. He says:

“So the real question is, how do we keep increasing our knowledge and control of the natural world without destroying ourselves and everything else on the planet in the process?”

As Crookes helped advance the need for increased nitrogen production, scientists everywhere today are calling for similar emergency innovations— technologies of control. We must control nature, we must control food production, we must control all of life. Why else would someone want to create “gene-silencing” nanoparticles? Why else would someone want to upend entire subsistence cultures in the name of predictability and uniformity? These technologies and ideologies are digging deep roots, roots which only our great, great grandchildren might know the ultimate consequences of.

Rather than asking why our food system is leaving nearly a billion people hungry every day, we create more “efficient” technologies. Rather than looking to the reasons for starvation, such as poverty, the inability to afford food, and food waste, we determined the answer is to just produce more food, and on and on the story goes. Instead of looking to our behavior and its endless extraction of nutrients from the soil and recognizing its inherent unsustainability, we doubled down on the behavior then, and are doing it still. We doubled down on our extractive ideologies, our scientific hubris, and our desire to control the natural world, while ignoring any of the societal factors that contributed to the problem in the first place.

So, the answer to the speaker’s question of, “how do we keep increasing our knowledge and control of the natural world without destroying ourselves and everything else on the planet in the process?” is both simple and complex.

We won’t.

If the epistemology that governs our conception of the world is that humans have the ability to control nature, we will never see a resolution to the problems our species faces. Is it not possible that if chemistry got us into this mess, that more chemistry will not get us out of it? Is it not possible that more technology will only further entrench us in a food system that is simultaneously wrecking the earth and severing us from our place within our ecosystems? Is it not possible that our scientific scheming to reverse climate change is coming from the exact same worldview as the scheming that created this problem of nitrogen?

A comment left under the video is prescient: “As Isaac Asimov once said, ‘The saddest aspect of society right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.’”

The inventions of today take on a life of their own tomorrow. When tinkering with nature, limits, and life itself, one has to know that the consequences will ultimately be dire. Whether with the intention of feeding the world, making money, or perpetuating national pride through the creation of bigger and better bombs, reversing climate change, or even just the advancement of our understanding of physics, scientists find themselves on the edge of a great void. Whether we like it or not, if they leap, we must follow.

This is why our podcast begins with the ominous words of Robert Oppenheimer, after witnessing the first detonation of nuclear bomb on July 16, 1945.

He says, with a haunted look in his eyes:

“We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed. A few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty and to impress him, he takes on a multi-armed form, and says, ‘Now I am become death: the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

As we all know, it remains to be seen if the world will be destroyed by nuclear weapons, though the revivification of a Cold-War atmosphere certainly occupies my mind. The look in Oppenheimer’s eyes — the tormented awareness that the world henceforth would never be the same — may not have captivated Fritz Haber’s conscious attention. His invention took time, and its immediate affects were not as undeniable as witnessing the blinding lights of the first nuclear bomb. The gut-punch of energy from the blast that would be the worldwide dependence on nitrogen fertilizer would come much later, long after his death, in the form of a globalized, colonial, industrial food system which renders near a billion hungry people utterly reliant upon foods that could only grow with this industrial process. What promised to be liberation became another arm of the imperial machine — something Haber could have only faintly known at the time. What Oppenheimer could see with his own two eyes, Haber only could have sensed, perhaps only in dreams or visions, what his invention would ultimately unleash upon the world.

The current food crisis is a result of economics, politics, colonialism, and capitalism — yes. But it is also a result of something particular that has been part of the human mind for thousands of years. The people knew Icarus was doomed by his hubris. Socrates feared the literate world would cease to remember. Likewise, the story of Genesis does not need to be “real” for us to take heed of its message. When Adam and Eve ate from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, we were cursed to toil and terraform the land, but why? We were cursed because we thought we could become Gods. Our curse was the belief that nature could be controlled by Man. In the quest for the Tree of Life, we got dangerously sidetracked and ate the fruit of the tree that God forbade us, as we would misuse the knowledge it gave us.36

“You may surely eat of every tree of the garden, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.”

Adam and Eve did not die — not then. But today we are bombarded with the news of end-time. Climate catastrophe is upon us, we’re told, and still we respond the same way as before, our eyes “opened” to our “rightful” place at the top of “The Great Chain of Being.” We still impose the ideology of control on the living world, this time, in the name of saving it. We continue to act as though the living world is a machine for us to tinker with. We’ve given up the pursuit of the Tree of Life and have allowed ourselves to be stuck within the curse that God placed upon us. Rather than looking to nature and it’s cycles, and understanding our place in the matrix of life and death, we continue the project of control and domination — further exerting the power of our inventions onto the living community, reducing the planet down to its constituent parts in order to “save” it. We eat unceasingly from the fruit of that tree every day. At some point, we’ll recognize the lunacy of this epistemology and we’ll stop fighting the unintended consequences of our pursuit for control with more control.

We may not be able to go back, un-eat the forbidden fruit, and start over where we began, but we can understand that this cycle we are stuck in is self-imposed. We can change our minds. We don’t have to continually scheme with the serpent, tinkering with life like it is a machine at our disposal. We can, and must, resume our search for the Tree of Life, but in order to do that, we need to accept one thing:

We are not in control here.

Written by Maren Morgan

If you would like to support the multimedia project “Death in The Garden,” please consider becoming a paid subscriber, or join our Patreon community. Thank you for reading.

Siebert, W. (1915) Journal Entry

Labatut, B. (2020) When We Cease to Understand the World

Hager, p. 160

Ibid, p. 27

Ibid, p. 35

Ibid, p. 52

Ibid, introduction

Ibid, introduction

Hager, p. 262

Mann, C.C. (2018) The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow’s World

Ibid, p. 107

Ibid, p. 108

Ibid, p. 153

Ibid

Ibid, p. 155

Shiva, p. 26

Ibid, p. 104

Mann, p. 172

Hager, p. 274

Mottet, A. et al (2017) Livestock: On our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2019) 2017 U.S. Nitrous Oxide Emissions, by Source

Schwabb, K. (2014) The Fourth Industrial Revolution

Shand, H.;Wetter, K.; Chowdhry, K. (2022) Food Barons 2022: Crisis Profiteering, Digitalization and Shifting Power

Ibid, p. 21

Ibid

Ibid, p. 34

Ibid, p. 47

Ibid, p. 25

Ibid, p. 21

Ibid, p. 24

Ibid, p. 25

Ibid

Quinn, D. (1992) Ishmael

i was vaguely familiar with the whole guano story and how all that came crushing down with a german invention. they called them "salitre" and "salitreras" in spanish . this is the whole detail of that story and i enjoyed it a lot, i wish more people knew this stuff.

keep it going!!

What an article! This should be a book.