Introduction

This past year, I turned to Jake and said I wanted to spend the weekend rewatching Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings. Though I had seen the trilogy many times before, something about the state that I was in made me see the films with eyes anew, and I saw them for what they are for the first time: cinematic masterpieces based on the most important archetypal story of our age.

Immediately I knew I needed to engage with this tale seriously for the first time, as I noticed themes within the story that I hadn’t adequately comprehended in the past: the themes of death and death avoidance, the themes of scouring lands, the themes of control, the themes of machines. I knew immediately that I needed to read the books, and I did so, for the first time in my life.

Currently, we are in a dearth of good stories. I know I’m not alone in feeling that we’re flooded with content without heart or substance. Many stories seem to be written by AI, or they rely on overwrought tropes and conventions that bore and annoy us, written by writers who are more concerned with audience engagement than actual passion for the story. When people conceive of “hero” stories, they often think of the formulaic opiate of super hero franchises and roll their eyes. They think of Mary Sue’s and their lack of actual character development. They think of the endless stream of A-list celebrities appearing in half-baked, repetitive stories with an increasing lack of coherence. They think of the pandering, the lack of sincerity and seriousness, the bright colors, and the idea of heroism by extension becomes lame, uninspiring, and ultimately unattainable without super powers or technology.

In this series I hope to convey the power and importance of stories, particularly stories which place an emphasis on heroism, love, and earnestness — stories that have received a bad name in recent times due to increasing cynicism and postmodern nihilism — as well as weakly written narratives that do not tap into these universally necessary qualities. I aim to show that in order for us to have the world that we desire: one of peace, of fellowship, and of connection, we need to start engaging with and creating new stories that reflect those themes.

Recently I have come to feel deeply that truth is best told through fiction, or in the words attributed to Albert Camus, “Fiction is a lie through which we tell the truth.”

What actually moves us? What provokes us to empathy, inspiration, and understanding? Art does. Stories do. And some stories which are created, adapted, or “sub-created”1 tap into the universal heartbeat of humanity and our place in the world. Whether they are mythic epics, or historical adaptations, or simple tales of humanness, there are certain stories that stay with us and compel us to interact with the world differently. If there is one thing that is undoubtedly true, it is that humans are capable of great good, as well as great evil. The stories that we tell ourselves play an outsized role in defining how we wield such power.

As film is the medium of our age, and many of us find ourselves in resistance to social media’s attempt at usurpation, I find it worthwhile to laud and critique current film media, as I have done previously. But, in order to do so for this series, I feel it’s necessary to lay this conceptual foundation with what is, in my opinion, modern fantasy’s magnum opus, and a myth that may just help raise us from such darkness: The Lord of the Rings.*

But first, we need to meditate on myths, and why we need them.

The Loss of Myth and Our Psychic Separation

Human beings are a lot of things, but one thing that seems to define us is that we are a myth-making, narrativizing species. Every cultural background of every group around the world has created some sort of unifying myth to help them understand where they are and where they are going, that is, until the modern age we currently live in. Science and technocratic rationality have taken over the role of an orienting principle in modern times, which leaves much to be desired in regards to the fundamental question that humans tend to have about life: what does it all mean? Painting with very broad strokes, moving from an animist worldview, to a more monotheistic worldview, then to a seemingly mythless secular worldview has left a great void in our understanding of ourselves and the world.

This breakdown of a theistic, religion-based order of course had some benefits. Liberation from theocracy, expansion of individual rights and autonomy, and widespread democracy followed this breakdown. But, as with many historical processes, the pendulum swung extremely to the opposite end, and now we are faced with a worldview that denounces the value of mythology, cosmology, and religious tales in favor of the primacy of the individual and “lived experience”, separated from context, nature, and ultimately, yet paradoxically, the self.

As Joseph Campbell wrote in The Hero with a Thousand Faces:

“The problem of mankind today… is precisely the opposite to that of men in the comparatively stable periods of those great co-ordinating mythologies which are now known as lies. Then all meaning was in the group, and the great anonymous forms, none in the self-expressive individual; today no meaning is in the group — none in the world: all is in the individual. But there the meaning is absolutely unconscious. One does not know toward what one moves. One does not know by what one is propelled. The lines of communication between the conscious and unconscious have all been cut, and we have been split in two.”2

What does Campbell mean by “there all meaning is absolutely unconscious”? What he means can be understood through a Jungian lens most easily — that there is a lack of integration between the ego and the unconscious. Balancing these two forces is the goal of self-actualization, but is quite difficult in our modern age. Leaving aside all of the relentless distractions we have, a typically modern person lives almost entirely within the realm of ego consciousness, disconnected from the connective fibers that exist between all things. Rather than perceiving ourselves as a beam of consciousness shooting up from The World Navel3 or axis mundi, we tend to view ourselves as individuals: as the central protagonists of the universe, disparate and unconnected to the whole. The ego, in order to ensure our own survival, orients itself around this pragmatic point of view for the simple reason that our connectedness to everything, psychically and physically, is irreconcilable with our desire to evade death. This puts distance between us and the mysteries of life, making us suspicious of the unconscious, which is indeed our portal to the understanding that may liberate us from the quest to evade death.

Myths, fairytales, dreams, imagination, and psychedelics offer us a doorway into understanding the unconscious, not only of ourselves, but of the collective wavelength we exist for a short time within. We’ve been split in two because of the primacy of the ego overshadowing the mysteries of the unconscious, making it difficult to accept our predicament as “a limited animal with unlimited horizons.”4 The unconscious, however, isn’t sleeping just because the ego is awake. It acts out in our reactions, our instincts, and our shadowy behaviors. Without the integration of the ego and unconscious, our destruction of the world, our separation and alienation from each other, and our psychic distress is likely to continue towards catastrophic ends.

“This is a new problem,” Carl Jung wrote in The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious. “All ages before us have believed in gods in some form or other. Only an unparalleled impoverishment of symbolism could enable us to rediscover the gods as psychic factors, that is, as archetypes of the unconscious… Since the stars have fallen from heaven and our highest symbols have paled, a secret life holds sway in the unconscious.”5

This “secret life” that emerges can be understood in the language of myth and story, which all contain archetypes. For instance, the archetype of the Victim may emerge in our unwillingness to take responsibility for our own lives. Or the Prostitute may emerge in the ways that we sell parts of ourselves to survive. Collectively, it’s helpful to look at myths such as Pandora, Icarus, or Prometheus to understand our human impulses and hubris, and how these parts of us can and have led us astray. But equally important, myths and stories show us our goodness and not just our faults. The story of Gethsemane, for example, offers us a glimpse into the unique courage that humans have when called to sacrifice themselves for the sake of the whole, in spite of our ambivalence and will to survive. Tales of bravery and selflessness have been marginalized considerably through this long process of disenchantment from myth; which, I, among many others, believe, will be key to recover moving forward through this age.

Jung famously asked, “What myth am I living?”6 The entire question of “What myth am I living?” as others have suggested, presupposes that we are living out myths, regardless of our conscious awareness of it. But it also bespeaks a latent power within ourselves to consciously bring into our own being particular myths — that there is choice in the matter as soon as we accept our role in the unfolding story of our time. The listlessness of modern man indicates that guiding myths can help us understand ourselves, and conscious integration of positive mythology into our lives can help us escape the unconscious myths that are tearing us apart and bringing us to the brink. What I would suggest in what follows, as an antidote to our collective “mythlessness”, is that we may glean such mythic inspiration from a more modern and beloved source.

The Lord of the Rings: The Myth for Our Time

“The Lord of the Rings gives three profound gifts to our time. All three of these gifts reflect Tolkien’s ability to recognize the mythic, enchanted quality of life: first, the recognition that the individual may be called upon to carry the weight of the whole, to bear the fate of the world; second, the reenchantment of the natural world, the recognition of the soul of nature which is filled with deep meanings and purposes; and the recognition of the battle between good and evil both in the external world and within each individual person.” - Becca Tarnas7

The Man Behind the Myth

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born in 1892 in South Africa, but grew up in England, facing incredible tragedies at very young ages in life. His father died of rheumatic fever when he was three, and his mother was left without resources to raise her two sons. Relying on the kindness of friends, and her devotion to the Catholic church, she was able to scrape enough money together to keep the boys fed and clothed. She taught her sons at home, instilling in them a love of botany, books, and encouraging young Tolkien’s love of languages and devotion to Catholicism.8

Tragically, when he was only thirteen, his mother would die young from type 1 diabetes. Thankfully, before she died, she placed her orphan sons under the guardianship of their priest, Father Francis Xavier Morgan. With his help and care, the boys were taken care of, and Tolkien was able to finish his studies and land a scholarship to Oxford. At Oxford, he would create a literary club consisting of him and three other young men who were his dearest and most beloved friends. The Battle of the Somme, when he was just 24 years old, would claim the lives of two of these treasured friends. His children would later describe how he occasionally would speak of, “the horrors of the first German gas attack, of the utter exhaustion and ominous quiet after a bombardment, of the whining scream of the shells, and the endless marching, always on foot, through a devastated landscape, sometimes carrying the men's equipment as well as his own to encourage them to keep going.”9

Trench fever contracted from the battle would ultimately save his life, invaliding him back to England. His sickness would prevent him from rejoining his battalion back in France, where most of the young soldiers were killed or captured in battle. This must have been a brutal period of time for him. Still, loving languages all his life, he studied Russian and worked on his Spanish and Italian while bedridden and healing. He would learn 19 languages in life, and invent 15 languages and dialects.

Tolkien would spend the rest of his life in devotion to his wife Edith and his four children, working as a professor of Anglo-Saxon and English at Oxford, studying and inventing languages, and of course, his gift to us all, excavating and then bringing to life the world of Arda, and the many tales of Middle-earth.

It should be noted that Tolkien did not write about Middle-earth as an allegory about the contemporary human condition. He disliked allegory, however, he understood that myths, fairytales, and stories often have allegorical interpretations — or rather “applicability” to the reader’s own life and understanding of their own mythos. In the 1965 addition of The Fellowship of the Ring in the forward he writes, presumably after an ungodly amount of questions regarding the tale being an allegory about the battle to defeat Hitler and Nazism:

“I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history, true or feigned, with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse ‘applicability’ with ‘allegory’; but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.”10

Nonetheless, in a letter written in 1951, Tolkien described to his friend that “myth and fairy-story must, as all art, reflect and contain in solution elements of moral and religious truth (or error), but not explicit, not in the known form of the primary ‘real’ world.” Therefore, in order to explain myths and fairytales, particularly ones which ring particularly true to the collective, allegorical language must be used: “the more ‘life’ a story has the more readily will it be susceptible of allegorical interpretations.”11

With all of this as a preface, and in spite of the many different ways one can interpret his vast legendarium, I would like to follow his own lead, in his own words, what the story is all about: Fall, Mortality, and the Machine.12

Fall, Mortality, & the Machine

Many others have endeavored to explore what is at the heart of the tale of The Lord of the Rings, and have done so beautifully. Some start their analysis with the Music of the Ainur and the god-creator, Eru Ilúvatar, or the sowing of discord in the world’s creation by the being who would later become Morgoth — regardless, starting right at the beginning.13 For the sake of brevity, and in an effort to bring forth my own analysis, I plan to begin our tale approximately 6,460 years before the hobbits leave the Shire.

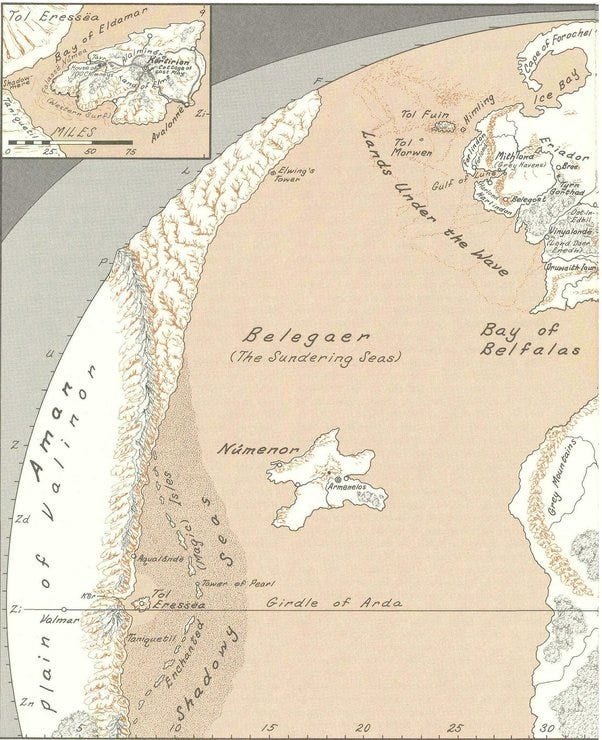

At the beginning of the Second Age, the Realm of Númenor was populated by a race of long-lived Men, of whom Aragorn is a descendent. The Valar, angelic beings on the planet of Arda, had granted Númenor to these Men as a safe haven, far from the perils of Middle-earth — a star-shaped island to the west of Middle-earth and to the east of the Undying Lands, known as Valinor.

The High Elves dwelled near to Númenor in Valinor, and they offered the Númenóreans many gifts and knowledges. But due to their mortality, the Valar banned them from ever crossing the western seas to the shore of Valinor. This was called the “Ban of the Valar.”14

When Men were created, they were created to be mortal. This “gift” of mortality was given to them as a blessing. The Valar considered this to be a gift because Men were able to perceive and understand the earth with a love that is punctuated most by the grief of having to leave it after only a short time. Being fated to death would allow them to grow as individuals and “have a virtue to shape their life, amid the powers and the chances of the world.” Elves, however, would be destined to the joy and sorrow of watching all the world grow and die around them. “For the Elves die not till the world dies” and thus they must watch all of the decay and changes of the earth without rest. For mortals, “death is their fate…,” writes Tolkien in The Silmarillion, “which as Time wears even the Powers shall envy.”15

Alas, the idea that this was a “gift” would fade through the centuries. Eventually, it became known as the “Doom of Men” and the Númenóreans, blessed with life “thrice that of lesser of Men” would come to be envious of the Elves’ immortality.16 This envy would come to permeate everything, and the fear of death spread through the kingdom, ever worsening through the age. Most of the society would be corrupted by this fear of death and anger toward the Valar for the Ban, save a group of Faithful who didn’t doubt the wisdom of the Gift.

“The Númenóreans began to hunger for the undying city that they saw from afar, and the desire of everlasting life, to escape from death and the ending of delight, grew strong upon them; and ever as their power and glory grew greater their unquiet increased… And the Númenóreans began to murmur, at first in their hearts, and then in open words, against the doom of Men, and most of all against the Ban which forbade them to sail into the West… But those that lived turned the more eagerly to pleasure and revelry, desiring ever more goods and more riches… They desired now wealth and dominion in Middle-earth, since the West was denied.”17

Over 3000 years pass, and during this time the Men of Númenor spread throughout Middle-earth, creating great cities; Sauron deceives the Elves and creates the One Ring; wars are fought against Sauron, and his mischief and evil deceives Men and Orcs alike. Realizing that he could not defeat the Númenóreans militarily, he allowed them to take him to back to Númenor as a hostage. There, he found the cracks in the people.

Their fear of death, envy of the Elves, and the desire to “overpass the limits to their bliss” was at a fever pitch when Sauron arrived ashore the island.18 The last centuries had been marked by a societal obsession: “the fear of death grew ever darker upon them, and they delayed it by all means that they could, and they began to build great houses for their dead, while their wise men labored unceasingly to discover if they might the secret of recalling life, or at least of the prolonging of Men’s days. Yet they achieved only the art of preserving incorrupt the dead flesh of Men…”19

Sauron was easily able to perceive their discontent, and lay the seeds of Men’s corruption. He convinced the king, Ar-Pharazon, that there were lands that remained unconquered, the sole province of Men. Sauron convinced him and his people that the god that ruled all creation was a false god, and the true god, Melkor — a god of order, deathlessness, and control— would give them the freedom and strength they desired.20 A civil war began between the Faithful and those who worshipped this “Giver of Freedom”, and Sauron convinced the Númenóreans to make “sacrifice to Melkor that he should release them from Death” leading to the deaths of thousands, bringing madness and cruelty into the land.21

“But for all this Death did not depart from the land, rather it came sooner and more often, and in many dreadful guises… Nonetheless for long it seemed to the Númenóreans that they prospered… For with the aid and counsel of Sauron they multiplied their possessions, and they devised engines, and they built ever greater ships. And they sailed now with power and armory to Middle-earth, and they came no longer as bringers of gifts, nor even as rulers, but as fierce men of war. And they hunted the men of Middle-earth and took their goods and enslaved them.”22

Finally, Sauron felt that the time had come to instill in the king the idea which would change the fate of Arda. He convinced the king that the Valar feared the Kings of Men and so lied to them about Valinor — that they feared Men would rule the world in their stead. He said that the Men of Númenor deserved to be immortal, rule the world, and that great kings should “take what is their due.”23 King Ar-Pharazon collected a great army and set for the shores of Valinor to take by force what he now believed to be his: the deathless life.

The Powers thus sent a great deluge and drowned all of Númenór for this crime against the laws of life. Luckily, a group of Faithful sailed toward Middle-earth just as the king made his fatal mistake. These men, led by Elendil, would become known as the Dúnedain, the friends of Elves, and they would fight Sauron in battle. Isildur, son of Elendil the Faithful, would cut the One Ring from Sauron’s finger and claim it as his own. This would end the Second Age.

Though Sauron was defeated, and for a time separated from the Ring, the race of Men would begin a long march of decay; the Elves would begin to fade; wizards would come to Middle-earth as counselors; and the Dúnedain would spend the centuries in secret as Rangers, waiting until the right time to reveal themselves and be worthy of taking the seat of Gondor as King. This Aragorn, son of Arathorn, Isildur’s heir would do, but only after two tiny hobbits from the Shire destroyed Sauron at last.

From this lesser known tale I hope it can be seen the importance of this story of the Fall and Immortality in The Lord of the Rings. The Age of Men, the Fourth Age, begins only when a heir of the Faithful sits upon the throne as King. I take this as Aragorn being emblematic as one faithful to the cycles of life and death — as a noble man who understands his place within the circles of the earth.

Aragorn’s death acceptance can be seen in his willingness to take the Paths of the Dead to acquire more soldiers for the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, in his love-story with the elf Arwen, and in his willingness to distract Sauron with his own life to give Frodo and Sam the chance to move undetected through Mordor. It is also represented in the manner of his leadership — not desiring power or domination, and only waiting until it is absolutely necessary to evoke his nobility and become King.

Though the will to power and domination precedes the Fall of the Men of Númenor, it’s plain that Tolkien intended us to understand that the fear of death and the yearning for immortality precedes the will to power and domination. In one of his letters he wrote:

“I do not think that even Power or Domination is the real centre of my story. It provides the theme of a War, about something dark and threatening enough to seem at that time of supreme importance, but that is mainly ‘a setting’ for characters to show themselves. The real theme for me is about something much more permanent and difficult: Death and Immortality: the mystery of the love of the world in the hearts of a race ‘doomed’ to leave and seemingly lose it; the anguish in the hearts of a race ‘doomed’ not to leave it, until its whole evil-aroused story is complete.”24

So how does the Machine factor into this story? He explains that the mythic idea of the Machine includes “all use of external plans of devices (apparatus) instead of development of the inherent inner powers or talents — or even the use of these talents with the corrupted motive of dominating: bulldozing the real world, or coercing other wills.” Tolkien, in this correspondence, loosely associated the Machine to “magic” though not the sort of fair magic of the Elves.25 Rather, I think, he was referring mostly to the magic of the One Ring — of which Sauron split an aspect of himself into to keep him from being destroyed, while also possessing anyone who attempted to claim it. This “apparatus” is consistently used to scour the lands of Middle-earth and coerce the wills of many races, namely Men and Orcs.

Those who possess the One Ring or are possessed by its power become servants of its will to order and dominate, though through a very interesting guise. Rather than it possessing one towards simple wickedness and evil, it possesses many through delusions of grandeur and the belief that it can be used for good. Saruman, who we’ll discuss at length later, wants to use the Ring so that the wizards could bring order and harmony to Middle-earth. This is why Boromir attacks Frodo, attempting to steal the Ring to win the war and protect Gondor. Sam is compelled, after taking the Ring from Frodo after Shelob’s sting, to see himself as owning his own garden the size of Mordor.26

In Tolkien’s Letters he states how Gandalf as the Ring-Lord would have been “far worse than Sauron.” Like Saruman’s delusion, he would have attempted to use the Ring to “rule and order things for ‘good’.” It is more dangerous, Tolkien writes, to be ‘self-righteous’ than ‘righteous.’27

It is clear that the Ring can never actually be used for good, and perhaps, by extension, that the emphasis of the Machine archetype in our own world, in the end, cannot be used for good either. And it’s true also that the Ring gives immortality to its wielder, as can be seen in the case of Gollum and Bilbo. In our world, it is plain that those who possess the “Ring” (the tools and apparatuses of wealth, technology, and power) are also obsessed by immortality.

There’s a lot of complexity around why and how the Ring effects its wielder. In the case of Bilbo, he acquires the Ring by theft, but also through an act of Mercy. He doesn’t kill Gollum because of his pity for the creature, which shields him from some of the more evil aspects of the Ring. Gollum, on the other hand, acquires the Ring through the murder of a beloved friend, thus his corruption is more absolute, selfish, and singular, and yet through the guilt, Gollum is split into two personalities.

Frodo, on the other hand, acquires the Ring with the mission to destroy it. This insulates him somehow to the powers of the Ring, until the very last moment when all life had been drained from him, and his resistance to its powers were at their lowest. Far from Frodo “failing” to destroy the Ring, it’s important to note that Frodo had long foreseen that he and Sam would not make the return journey from Mordor, so the promises of immortality, at that final moment, would have been most pronounced for Frodo as a survival mechanism. This is where I believe many critics are incorrect about what the Ring represents: it does not represent death, it represents our attempts to evade death, which inevitably brings about more death. If the Ring represented death, then the quest would be to destroy death — a ridiculous and impossible task, and one which contradicts so much of how death is approached in the tale.

For instance, in Tolkien and the Critics, Hugh T. Keenan wrote that Frodo’s inability to destroy the Ring is his giving in to death — that Frodo “loses his zest for life.”28 But this analysis suggests that a Freudian thanatos impulse is stronger than the eros impulse, which, in my view, doesn’t make sense. He was already fated to die in Mordor, and had used every last drop of life he had to get there. The will to live, even with a conscious knowledge of the deception of the Ring, is the only thing, in my view, which would have him abandon his quest at the last moment.

The idea of thanatos and eros is a duality that is fundamentally incomplete without conjuctio or coincidentia oppositorum — a unity of the opposites. Keenan writes that the reason the hobbits were given the greatest burden to bear in the destruction of Sauron is because “they prove to be the human-like creatures most interested in preserving life… They represent the earthly as opposed to the mechanic or scientific forces. Therefore they are eminently suitable heroes in the struggle of life against death.”29

While the hobbits being the only ones capable of this act is absolutely true, I still question the subtle premise: is life actually opposed to death?

To be close to life inherently means that one is close to death, as all farmers, pastoralists, or indigenous people can attest to. Therefore, it’s important to be clear — Sauron’s wickedness comes from his deception to mortals that the world can be ordered and controlled so as to banish death. His distain for “things that grow” may come from this death denying ambition, as all that grows must die in time. The Ring’s powers challenge the will of Men the most, who, by their Fall from Númenor show us that it is not only the power the attracts them, but the promise of immortality. The Hobbits are the least likely to be possessed by it because as beings in closer devotion to life, they do not fear death as they know it is essential for more life. When the unity of the opposites (death and life) are achieved, one finds himself less susceptible to the evil that the Ring represents, as is also in the case of Aragorn.

It’s plain that there are many layers to Tolkien’s meditation on these themes of Fall, Mortality, and the Machine. One of the most important aspects of the idea of the Machine in the story comes in the form of Saruman.

A Mind of Metal and Wheels - Saruman and T.I.N.A.

When Gandalf the Grey discovers the One Ring in Bilbo Baggins’ possession, he seeks the counsel of Saruman the White to understand how to destroy it. Instead, to his shock, he finds a Saruman who has been completely corrupted by Sauron’s whisperings and the powers of the Ring.

Saruman tells him the importance of them taking ownership of the Ring. Saruman tells Gandalf that the age of Men is upon them, and that they must rule them. “But we must have power,” Saruman says, “power to order all things as we will, for that good which only the Wise can see.” He explains that joining with Sauron and with the power of the Ring is the only way toward hope and victory.

He says:

“As the Power grows, its proved friends will also grow; and the Wise, such as you and I, may with patience come at last to direct its courses, to control it. We can bide our time, we can keep our thoughts in our hearts, deploring maybe evils done by the way, but approving the high and ultimate purpose: Knowledge, Rule, Order… There need not be, there would not be, any real change in our designs, only in our means.”30

Gandalf rejects this offer, and is imprisoned by Saruman.

Saruman is an very interesting character, as his betrayal stems from the belief that, not only could he wield the Ring for good, but that there is no alternative (or T.I.N.A.) when it comes to the Power of Sauron. For him, it is better to align with this Power and attempt to direct its flows towards what he deems good: Knowledge, Rule, and Order. Explicitly, he is saying that this evil cannot be fought, and through wielding it toward good, the ends justify the means. Though, again, Saruman is not written as an allegory for anything in our world in particular, I think we can glean wisdom from his failings.

The idea of “T.I.N.A.” was first introduced to me by Paul Kingsnorth in a Substack essay. When we interviewed him in person, we asked him about T.I.N.A. and he said:

“I think it's one of the most powerful stories that we have that sustains the industrial system, because we believe it. And the reason we believe it is that we can look around ourselves and we can quite rightly say, well, how are we supposed to get out of this enormous system that we've built? And there isn't any obvious way to do that. And like the progression of the green movement from being a radical movement, to being a co-opted corporate movement, you have a group of people who say, well, look, really the only realistic thing to do is to continue doing what we're doing, but try to make it more sustainable, make it more green… We can't really change our way of seeing — we can't challenge science. We can't challenge technology. We can't challenge this, that, and the other, ‘that's just Luddism and romanticism and naive silliness.’ It can't be done. The realistic and grownup thing to do is to make the machines sustainable… So the notion that there isn't an alternative to the way that we see things is enormously powerful as a kind of propaganda mechanism, really. And we've all internalized it, really. We look around and we say, ‘Yeah, it isn't realistic to live differently,’ which of course is how the thing is sustained.”

And so Saruman fells all the trees of Isengard to fuel his war machine. As Treebeard describes him, “He has a mind of metal and wheels; and he does not care for growing things, except as far as they serve him in the moment.”31 He creates a tremendous and terrible army, and ultimately his betrayal leads to his own destruction.

Here, I think it’s valuable to share where the books and Peter Jackson’s film differ. In the films, Saruman has dammed the river Isen to generate power for his war factory in Isengard, which the Ents destroy, causing a deluge to flood Isengard and kill all of the Urukai who were defending the tower Orthanc. In the books, the Ents make makeshift dams themselves to flood Isengard. This liberty taken on the part of Peter Jackson is important, because it shows another way of attempting to control nature for one’s own ends. The living land of Middle-earth — symbolized by the Ents and the un-damming of the river — cannot be ordered, simplified, and controlled in such a way as Sauron and Saruman wish, just as our own world resists. Therefore, we return to the truth that death is only a consequence of the quest for control and domination. Take this description of Isengard following Saruman’s treachery:

“Once it had been fair and green, and through it the Isen flowed, already deep and strong before it found the plains; for it was fed by many springs and lesser streams among the rain-washed hills, and all about it there had lain a pleasant, fertile land…It was not so now. Beneath the walls of Isengard there still were acres tilled by the slaves of Saruman; but most of the valley had become a wilderness of weeds and thorns. Brambles trailed upon the ground… No trees grew there; but among the rank grasses could still be seen the burned and axe-hewn stumps of ancient groves. It was a sad country, silent now but for the stony noise of quick waters.”32

Sauron and Saruman would scorch all the earth, denuding it of all life, for their ends — doing whatever it takes to secure their victory. To me, this also leads to another very revealing letter of Tolkien’s, wherein he explains that:

“If there is any contemporary reference in my story at all it is to what seems to me the most widespread assumption of our time: that if a thing can be done, it must be done.”33

This assumption combined with the story of T.I.N.A. gives nearly unlimited leeway for the decisions we make to either destroy an enemy, progress technology, (or even save the world) in our own world. But this reality also gets at the heart of what makes The Lord of the Rings such an important story in our time. As Randel Helms explains in Tolkien’s World:

“From the end of the Middle Ages to the first nuclear explosion (to be overly precise) our deepest spiritual urges have been Faustian, directing our emotional and intellectual energies in an endless quest for knowledge of and power over nature, over our world. Now we have become like Sauron; we can control nature, but we find in the process that every controlling touch spoils and corrupts. Like Sauron, we can darken the sky, blast the vegetation, pervert and even control the minds of men; and again like Sauron, we remain prisoners of our own assumptions, seeing no alternative to ever expanding our corrupting control.”34

Anti-Faustian Tale

Ernest Becker, in his posthumously published book, Escape From Evil, used similar language as Helms to describe civilization’s trajectory over the age:

“…the hope of Faustian man was that he would discover Truth, obtain the secret to the workings of nature, and so assure the complete triumph of man over nature, his apotheosis on earth. Not only has Faustian man failed to do this, but he is actually ruining the very theater of his own immortality with his own poisonous and madly driven works…”35

I have written before of our Faustian impulses which followed the Enlightenment, and which reached a fever pitch in the early 20th century. But I would disagree that this pattern of behavior ended with the atomic bomb — in fact, it has only gotten stronger as the times become more and more perilous. Helms wrote Tolkien’s World in 1974, but from my vantage, there has been little to no slowing of the Faustian impulses of our society in spite of our increasing awareness of how destructive industrial civilization is. Instead, we have only become more and more entangled in the creations by men who created just to see if they could, and the stories they tell about those creations to keep us trapped.

This is why there is so much wisdom to be gleaned from The Lord of the Rings. As an anti-Faustian tale, we witness our heroes constantly be tempted by the Ring, and time and again, their inherent goodness prevails and they resist. If not for Frodo’s pity and goodness and Sam’s mercy towards Gollum, the Ring would have lived on, returned to Sauron to cover the earth in his wicked order. If not for all of the other heroes in their rejection of the Ring, tyranny would have prevailed.

If Tolkien had written the books as an allegory, evil would have ultimately prevailed. In some way, the Ring would have passed from victor to victor again and again, scorching and scarring the lands and peoples for time immemorial. But Tolkien did not write an allegory: he wrote a myth.

Here’s more of Tolkien’s response to the charge that he was inspired by World War II in writing The Lord of the Rings:

“If it had inspired or directed the development of the legend, then certainly the Ring would have been seized and used against Sauron; he would not have been annihilated but enslaved, and Barad-dûr would not have been destroyed but occupied. Saruman, failing to get possession of the Ring, would in the confusion and treacheries of the time have found in Mordor the missing links in his own researchers in Ring-lore, and before long he would have made a Great Ring of his own with which to challenge the self-styled Ruler of Middle-earth. In that conflict both sides would have held hobbits in hatred and contempt: they would not long have survived even as slaves.”36

It is clear to me, therefore, that The Lord of the Rings is an idealistic tale, one that believes in the inborn goodness of Men — but that Tolkien was also not naive to Men’s weakness. Living through the trials and tragedies that he did, seeing the horrors of World War I and II as he did, one would think that he would be pessimistic about Men, but no. I believe he knew, that in spite of our weakness, we need tales that show how we overcome those weaknesses.

We are deeply influenced by the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. In writing an anti-Faustian tale of ordinary and extraordinary heroes, we’re compelled to see ourselves more clearly in our potential, in spite of the struggle that may arise when great deceptions tempt us. As Becca Tarnas wrote, “The struggle, or battle, of life is to recognize and overcome this evil present not only in the external world but also, more importantly, within ourselves.”

We see this struggle embodied in a number of ways: namely, through Boromir’s desire to acquire the Ring for the glory of Gondor. But it remains implicit in the story that there is nothing evil about Boromir for desiring to use the Ring for good — only that all Men or other creatures of Arda can be deceived by stories. Tolkien makes clear to us that Boromir’s soul is untainted by his attack on Frodo, that he is forgiven in his repentance before he is slain trying to defend Pippin and Merry against the Urukai.

In this tender moment we see that often, for us to reach our fullest knowledge of our truth and goodness, we must also see our deepest and most regretful shadowy parts. As Thomas Hardy said, “If a way to the better there be, it lies in taking a full look at the worst.” There is no pessimism about the weakness in Men in the story of Boromir — instead we are confronted with the truth that even our good intentions and strivings can lead to evil deeds, which Boromir learns firsthand. Through him, we can learn this of ourselves. Tolkien is showing us that the most noble act is in resistance to the Faustian story, especially when it is most difficult.

Beyond this, beyond seeing our weaknesses be overcome through the characters of this story, this story is full of heroism — the sort of heroism that doesn’t over-emphasize the individual and instead shows us how we all have a role to play in overcoming great odds and great evils. As Gandalf says, “only a small part is played in great deeds by any hero.”37

Heroism in the Time that is Given to Us

All of the characters in The Lord of the Rings have an incredible role to play in the destroying of the Ring and the vanquishing of Sauron. They all rise to the occasion to sacrifice themselves to protect the world that they love. Our modern age feels imperiled, and we too look around ourselves and wonder what we can save, how we might be the heroes that the world needs. And yet, we might also wish that we were born in some other time, with some other hardships. We may wish, as Frodo did, that the Ring never came to him, that such Shadow had never enveloped him. In one of the best lines from both the films and the books, Gandalf gives this reply to Frodo:

“So do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.”38

We were all born in this time for a reason, as our heroes were alive at this time in the history of Middle-earth for a reason. They all have a role to play, and without one another, the task would never have been completed. It is of dire importance that we see ourselves in this story because without it, we may believe that all hope is lost and succumb to despair. As Tolkien wrote, it may be the case that “the ‘good’ of the world depends on the behavior of an individual in circumstances which demand of him suffering and endurance far beyond the normal.”39 Perhaps this is true for all us ordinary people who look around and see a world in dire need of care. Perhaps the call is for all of us to learn to be more heroic.

Through the ordinary heroism of Frodo and Sam, we learn the value of friendship and bravery against all odds. Through the noble heroism of Aragorn, we see the value of self-sacrifice and facing one’s death to rise to the fullest of one’s potential, for the good of the whole. Through the feminine heroism of Éowyn we see the virtue of protection and love as our greatest weapon against evil, and that there is far more honor to be had in life than glory in battle. Through the grieving heroism of Théoden King of Rohan, we learn, again, the value of not being so fearful of death that we avoid life.

The heroism and love on display in The Lord of the Rings invigorates us, which is why these books and films are some of the most beloved in all of human storytelling. The archetypes of the characters somehow touch a place within us that feels true and honest, whereas other stories, such as many modern superhero movies, don’t. If stories help us understand our time, it’s worth noting the timelessness of the books as well as the films. Tolkien and Jackson both captured something eternal about our need for heroism, a need, which anthropologists like Ernest Becker considered to be innate.

To Becker, we create “hero systems” as a means of alleviating our death anxiety, or our impulse toward immortality — and these hero systems have laid waste to landscapes and have led to the death of billions of people over the course of history. In light of this, does Becker then suggest that we destroy our hero systems? Not at all.

“Man cannot abandon the heroic,” he writes in Escape From Evil.40 Rather, we need to accept this reality of being human — that we are myth-making, narrativizing, story-telling animals. “If men live in myths and not absolutes, there is nothing we can do or say about that,” he continues. “But we can argue for nondestructive myths.”41

So I am arguing for this myth, The Lord of the Rings, to be the emblematic nondestructive myth of our time. As Helms wrote:

“A hero is the expression of a culture’s ideals about itself, and our ideals about ourselves have all been punctured. Cultural ideals are formulated and understood most efficiently in myths, and we have lost the ability to participate wholeheartedly in mythic belief... And that loss, tragic as it is in its own right, opened the door to one that seems to me even great: a bone-deep cynicism about, a frostbitten insensitivity toward, the capacities of myth for discovery, for transmission of awe, and for molding a worthwhile self.”42

This tremendous loss is what has led us to this dearth of good stories and lack of meaning in our modern age. It breeds the most destructive forms of cynicism and misanthropy, and we perpetuate it through the stories we write and consume. We need not be influenced by the listless, postmodern nihilism that hero stories aren’t worth telling, or that they aren’t reflective of the truth of Men. Helms writes that it is imperative that we tell fantasy stories that are worthy of us, that show a “vision of man’s potential nobility.”43

I think this is why The Lord of the Rings is such a timeless story. Beyond the themes that I’ve outlined of Fall, Mortality, and the Machine, Tolkien shows us a heroism that is relatable while also dignified, aspirational while also tangible. We can see a bit of ourselves in all of the characters, and feel inspired by how they respond to their trials. They are imperfect, but at root, we understand them to be good, just how, I think, at root, we understand ourselves to be good. We know, somehow, that our darkness is part of us, but not all of us. That there are light and beautiful parts of us that “no shadow can touch.”

If we cannot avoid our hero systems, why wouldn’t we seek to create or embody good ones? Why wouldn’t we want to write good stories? No, great stories.

Conclusion

When I decided to take The Lord of the Rings seriously, something concretized in me that is lasting and incredibly important — something that is all-too-easy to forget these days: “that there is good in the world, and it’s worth fighting for.” I think the reason so many people love these books and movies is because it awakens something similar in them as well. This tale transports us to a world filled with meaning, life, and connection. I could have written so much more about this story and the histories of the world of Arda, as there is so much to say — so much to admire. This work of pure, essential imagination that Tolkien discovered somehow feels more real than the world we live in. In spite of the trials, it seems a better world.

Tolkien, in his tale, invites us into greater participation with our own world through the animist enchantment of Middle-earth. The trees and winds don’t just speak to Elves: they can speak to all who take the time to listen. The disenchantment of our world is pernicious, but not yet thorough, not so long as there is art that reminds us of the beauty in the world. As he describes in On Fairy Stories, though fantasy stories can be seen as “escapism”, there is a great deal of difference between The Escape of the Prisoner and Flight of the Deserter.44

“It is part of the essential malady of such days producing the desire to escape, not indeed from life, but from our present time and self-made misery— that we are acutely conscious both of the ugliness of our works, and of their evil,” he writes, with great empathy to the imprisonment of those alive in his time, and by extension, in our time.45 As Becker explains, “today we are living the grotesque spectacle of the poisoning of the earth by the ninteenth-century hero system of unrestrained material production. This is perhaps the greatest and most pervasive evil to have emerged in all of history, and it may even eventually defeat all of mankind.”46 It is understandable to want to escape such a reality from time-to-time.

But good stories, like living a good myth, as understood through the Hero’s Journey, involve an essential element: one goes on the adventure, escaping their regular humdrum and perhaps miserable existence, to ultimately return with a gift to share. It is the deserter who never comes back — who never shares what he has learned on his journey. The same can be said of us: when we escape into content or cheap entertainment, what boon do we really bring back? Why, so often, do we come back empty?

Perhaps it is the case that we are all prisoners of a toxic hero system, hell-bent on the destruction of the world, our sense of purpose, and our enchantment with life. Escaping such a hero system will be perilous, filled with many dangers and much darkness. But so long as we do not desert our responsibility to the task, as long as we retain our belief in the goodness in the world, there is no shadow too dark, nor evil too absolute.

Written by Maren Morgan

Thank you so much for reading this piece. If you enjoyed it, please like and share it with the people in your life.

If you want to support Death in The Garden, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or giving us a one-time donation. The links that are included in the sources below are affiliate links, so if you use those, we get a small kick-back. If you already support us financially, thank you! Your support is the only thing that makes this project possible. Stay tuned for the audio and video version of this essay — available soon!

Also stay tuned for Part II and Part III of this series. In the next part, I will break down the corrosive myths that are perpetuated through postmodern storytelling, including through reality TV and antiheroes, and I’ll offer real-life tales of heroism and fellowship as a counter-example.

*Note to readers: I wrote this piece following an assumption that most people basically know the story of The Lord of the Rings to not overburden my analysis of the themes with too much exposition or explanation of what happens in the story. I took time to describe in much greater detail information that can only be found in the Appendixes of The Return of the King and The Silmarillion because those are lesser known stories and were key to my analysis, but I have tried to make them accessible to a broader audience. I explicitly do not reference Amazon’s The Rings of Power because it does not follow at all the essential mythos of Tolkien’s story and utterly lacks storytelling depth. For the most part, I speak of the books and films interchangeably, except in discussing the parts that are different enough to warrant clarification. While this is written to be enjoyed in its current form, the emotional impact of this piece will invariably be better suited for audio and visual media. I highly recommend that readers read this piece on the Substack website or in the app to be able to more easily watch the videos I have embedded. This is by no means a concise or complete breakdown of the mythology of The Lord of the Rings — to do so would take even more time than this has already taken.

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1939) On Fairy Stories, p. 34

Campbell, J. (1949) The Hero with a Thousand Faces, p. 334

Ibid p. 32

Becker, E. (1975) Escape from Evil, p. 153

Jung, C.G. (1959) Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, p. 23

Jung, C.G. (1951) Symbols of Transformation, p. xxv

Tarnas, B. (2005) A Myth for Our Time: The Work of J.R.R. Tolkien

McDonald, A.I. (date unknown) introduction of Leaf by Niggle by J.R.R. Tolkien, p. 9-11

Tolkien, J. & Tolkien, P. (1992) The Tolkien Family Album

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1965) The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, p. xi

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1892-1973) The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien: Letter 131, p. 143

Ibid p. 145

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1977) The Silmarillion: “Ainulindalë”, p. 26

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1965) The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, p. 390

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1977) The Silmarillion, p. 51

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1965) The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, p. 390

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1977) The Silmarillion, p. 330-334

Ibid p. 330

Ibid p. 334

Ibid p. 340

Ibid p. 342

Ibid

Ibid p. 343

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1892-1973) The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien: Letter 186, p. 246

Ibid p. 146

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1965) The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, p. 216

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1892-1973) The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien: Letter 246, pg. 332

Keenan, H.T. (1968) Tolkien and the Critics: Essays on J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings - “The Appeal of The Lord of the Rings: A Struggle For Life”, p. 70

Ibid p. 66-67

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1965) The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, p. 340

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1965) The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, p. 90

Ibid p. 186

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1892-1973) The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien: Letter 186, p. 246

Helms, R. (1974) Tolkien’s World, p. 60

Becker, E. (1975) Escape from Evil, p. 72

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1965) The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, p. xi

Ibid p. 353

Ibid p. 82

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1892-1973) The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien: Letter 181, p. 233

Becker, E. (1975) Escape from Evil, p. 159

Ibid p. 159-160

Helms, R. (1974) Tolkien’s World, p. 150

Ibid p. 151

Tolkien, J.R.R. (1939) On Fairy Stories, p. 30

Ibid p. 32

Becker, E. (1975) Escape from Evil, p. 156

Very excited to finish reading this. I just rewatched the trilogy a couple weeks ago and had so many of the same feelings. They were my favorite films for years but I was affected at a much deeper level this time—the level of myth. I am reading the books now for the first time.

Rewatching Lord of the Rings tonight